We have seen the red-jumpsuit-wearing, scissors wielding, disturbingly feral enemy and they are...us? So it does appear in the second film from the enormously successful Jordan Peele. Mr. Peele has given us another horror film of sorts, one in which the doppelgangers, the ones in the jumpsuits, are none to happy. And who can blame them, really?

For starters, this apparently large population of doppelgangers has been waiting. A long time. A pre-title sequence goes to some pains to let us know, both explicitly and with tokens of Reagan Administration America, that it's 1986. Like Josh Baskin in Big, little Adelaide Thomas (Madison Curry), wanders toward a mysterious, set apart attraction at a boardwalk carnival and much chaos ensues several decades on.

Adelaide enters a kind of funhouse called "Find Yourself." There's something of a Native American theme to this attraction, and we hear a Native American voice speaking as the little girl wanders into the building, before confronting her doppelganger amid a hall of mirrors. Is the Native American motif significant in a story that's supposed to be all about duality, aggrieved people tethered to their more fortunate brethren? Perhaps. But like so many elements in Us, it's just another signpost of significance leading us nowhere.

Time, like so many pesky elements of storytelling, is handled in a matter both fast and loose by Mr. Peele. We are indeed led to believe that the pissed off doppelgangers have been plotting their revenge, not to mention Hands Across America II since 1986. But what of this population of doppelgangers? Are they all related to people who unwittingly wandered into "Find Yourself" or perhaps similar funhouses? Might some of this population have been waiting longer? And how about the golden shears and the red jumpsuits on which they apparently got a volume discount?

|

| Don't you hate it when your nice day at the beach is spoiled when a red-jumpsuit-wearing doppelganger family shows up in your driveway that night? Just some of the tethered ones in Us. |

Well, while the doppelgangers sort out matters of wardrobe and choreography, little Adelaide Thomas grows up to become Adelaide Wilson in the present day. Here, the welcome presence of Lupita Nyong'o. It's thanks to Ms. Nyongo's considerable talents that when Adelaide's so-called tethered character, "Red," appears at their suburban home, the doppelganger manages to seem more scary than Internet meme waiting to happen (of course, the film has inspired dozens of such memes by now). No small feat, as Nyong'o has to fairly belch out words staccato from the depths of her vocal register while maintaining a menacing glare from dilated eyes. But for a time, it works, as does Us in a limited way.

|

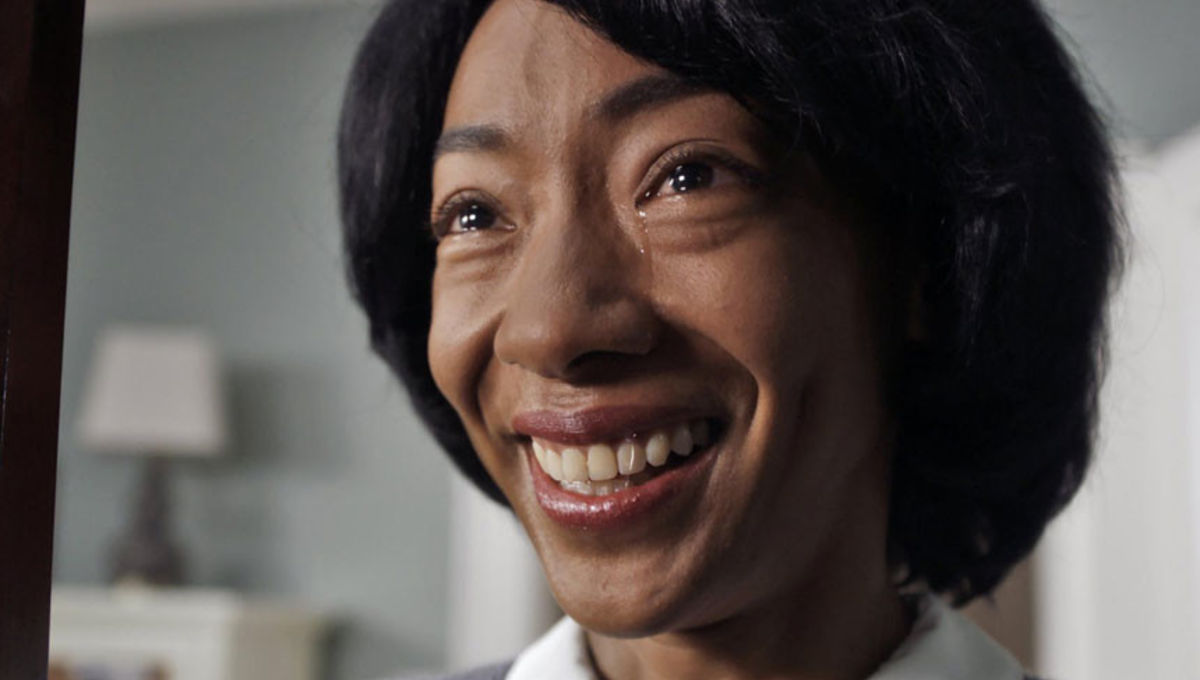

| Betty Gabriel, so memorable in Jordan Peele's Get Out (2017). |

As was the case, if more indelibly, in Get Out (2017), Peele does well with stark images, as when the other Wilson family shows up. Cheap thrills are to be had with sudden motion and sound effects, but silence and the static presence of something intent on malice is often more deeply unsettling. While the frightened, seemingly normal Wilson family cowers inside their well-appointed home, dad goes out to get rid of the interlopers, first with reason, then brandishing an aluminum bat. Red, the momma doppelganger, then makes a clicking sound and her version of the family fans out for attack, clearly a well-drilled bunch.

When the doppelgangers finally corner the Wilson family in their living room, they are met with the question that any of us might proffer to an insurgent group of alternative selves, distinguished by their simple if menacing fashion sense: who ARE you? The answer? "We are Americans." So squeaks or belches Red. And why the goofy voices? one might ask. Us might have been more appropriately entitled Why? Or Huh? On the dubious scale of pretense, this isn't quite as bad as the protagonist in Andrea Arnold's (dreadfully overrated) American Honey (2016) exclaiming (from a convertible, no less), "I feel like I'm fucking America," but it's still pretty laughable.

|

| Batting cleanup for the Doppelganger All-Stars, Abraham! The other Wilson family in Us. |

So, what of these squeaking, grunting (father doppelganger Abraham doesn't have much to say; men!) relentless Americans? Are they the lesser selves of the Wilson family? Or perhaps the unfortunate, less privileged version? Doppelganger D-Day occurs after the Wilson family return from the beach at Santa Cruz, the location of little Adelaide's no-so-funhouse adventure those several decades earlier.

The family Wilson visit the Tylers while at the beach, the father of which family Gabe Wilson (Winston Duke in the double role of Gabe/Abraham) seems to compete in terms of worldly wealth. The Tylers, who happen to be white, are clearly a bit more crass, both in terms of behavior and conspicuous consumption. You might hear that Us is about race, class and other significant issues. The film seems to aspire to that sort of gravitas, while giving us all a good scare. Sadly, it's not clearly about anything.

One might be inclined to interpret aspects of the story in terms of one class unfairly elevated above another, or as parable in terms of the African American family unwise to get lost in the commercialism of the larger and generally more affluent population of white America. But Us short-circuits any deeper meaning with its own haphazard wiring of plot lines.

Of course, it looks pretty dire for the Wilson family when their fearsome doppelgangers show up and drag them all to respective corners, as it were. But wouldn't you know it? - the Wilsons are a pretty plucky bunch and all make an unlikely escape, reconvene and speed away from the house, daughter Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) happy to take the wheel of the family's SUV. There's a kind of subsequent debriefing, during which this family in no way demonstrates the sort of post-traumatic doppelganger disorder that any semblance of logic would dictate.

There was so much good, even brilliant about Get Out, that it was easy enough to forgive the film its reversion to horror movie conventions as it progressed...at least until the highly unfortunate feel-good conclusion (whether the decision of the director or imposed from the studio or others holding the purse strings). But that slightly jokey interval with the Wilson family feels like nothing more than a kind of break for the audience, lest they begin to grow truly unsettled...or perhaps just bored despite the carnage. It's not a playing with convention, but a succumbing to convention. It's the cement shoes of Hollywood. To see films that manage to coherently and artfully mix carnage, wit and social commentary, while still adhering to some semblance of logic, please refer to Edgar Wrights "Cornetto Trilogy," particularly the first two entries in the series, Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Hot Fuzz (2007).

We get to see the Tyler family a second time in Us. Alas, there's no sanctuary to be had amidst the comfort of Chez Tyler, because their own set of doppelgangers show up as well. Fortunately, this set of malicious Tylers has a good sense of dramatic timing and doesn't attack until Wilson family and the cameras arrive. Ready to do some heavy lifting, some murdering and being murdered, is the ever-versatile Elizabeth Moss, playing both Kitty Tyler and tether mother, Dahlia. As with the redoubtable Ms. Nyong'o, Ms. Moss manages to lend Us some temporary authority.

For whatever reason, it's clearly not only the Wilson family beset with tethered selves, but those obnoxious Tylers as well. And perhaps every family in California? In America? And what of the single, the lovelorn? Are they, like the virgins of horror films of old, to be spared? We are made privy to a news report on television that the menace is widespread, with accounts of further carnage and the strange forming chain of the red-jumpsuit-wearing figures. And here we begin to approach an M. Night Shyamalan level of absurdity and inadvertent comedy.

A shame, because some of Mr. Peele's ideas, some of his images, do seem rich with possibility. With Get Out, he created a film of mainstream appeal in which thorny issues of race were not only front and center, but focused less on blatant racism than sinister appropriation, instances of which almost never enter the discourse of popular culture.

A shame, because some of Mr. Peele's ideas, some of his images, do seem rich with possibility. With Get Out, he created a film of mainstream appeal in which thorny issues of race were not only front and center, but focused less on blatant racism than sinister appropriation, instances of which almost never enter the discourse of popular culture.

The obvious thing in Get Out would have been to refer somehow to common examples of white culture appropriating dress, language and music. This is somewhat true of the Tylers in Us, amusingly hoisted on that petard. When they desperately command their Siri-like device to call the police when their doppelgangers appear, the virtual assistant instead plays NWA's "Fuck Tha Police," a good bit of which we hear. In Get Out, Peele took such notions a step further with appropriations of the actual flesh and bones of African Americans and for a time married that conceit brilliantly with the framework of a horror film.

There's a moment in Us when Dahlia, the tethered one to Kitty Tyler, prowls about the house, menacing all in her path, including Adelaide. Taking a short break from the mayhem, Dahlia plays with a lipstick. Elizabeth Moss in this moment manages to convey a being both feral and child-like in her manic enjoyment of the ritual.

In such rituals, in similar matters of makeup, skin and appearance, there would seem to much potential for that deeper of level of meaning after which Us so frequently gropes but fails to grasp. There is not only the expectations placed upon women and their appearance, not simply skin colors over which people are divided, for which they're discriminated, but also the varying skin tones by which African Americans are judged and sometimes divided, from within and without. Lupita Nyong'o has spoken on the latter topic with some eloquence. But in Us, it's just another lost opportunity.

As Us stumbles into it's silly, subterranean climax, the problem isn't just a complete lack of logic, it's a film that can't even succeed on it's supposedly scary surface. Last year's Mandy from director Panos Cosmatos was not exactly a masterpiece. It became even more ludicrous as it tried to explain things...like its demon bikers for instance. While story is apparently not Mr. Cosmatos' strong suit, Mandy held one's attention to the gory end, thanks in part to the director's vivid, feverish visual sense and a classically wack performance from Nicolas Cage. With Us, we're left with only a lot

of half-baked allegory and a final helicopter shot of red-suited doppelgangers inexplicably reenacting Hands Across America. Watch out for those wildfires, oh tethered ones! The real California can be much more scary than anything dreamed up in this film.

The only clear moral of the story here seems to be that when visiting those boardwalk or pier carnivals, those charming old attractions, best that we confine ourselves to the well-lighted midways, best to keep the little ones safe from the siren song of the mysterious fortune telling machine, the ominous fun house. How about a nice game of skee ball? Perhaps some Whac-A-Mole? That might be the best thing for all of us.

|

| Nice rock, huh? Elizabeth Moss in Us. |

One might be inclined to interpret aspects of the story in terms of one class unfairly elevated above another, or as parable in terms of the African American family unwise to get lost in the commercialism of the larger and generally more affluent population of white America. But Us short-circuits any deeper meaning with its own haphazard wiring of plot lines.

Of course, it looks pretty dire for the Wilson family when their fearsome doppelgangers show up and drag them all to respective corners, as it were. But wouldn't you know it? - the Wilsons are a pretty plucky bunch and all make an unlikely escape, reconvene and speed away from the house, daughter Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) happy to take the wheel of the family's SUV. There's a kind of subsequent debriefing, during which this family in no way demonstrates the sort of post-traumatic doppelganger disorder that any semblance of logic would dictate.

|

| Daniel Kaluuya in Get Out; Lupita Nyong'o in Us. |

We get to see the Tyler family a second time in Us. Alas, there's no sanctuary to be had amidst the comfort of Chez Tyler, because their own set of doppelgangers show up as well. Fortunately, this set of malicious Tylers has a good sense of dramatic timing and doesn't attack until Wilson family and the cameras arrive. Ready to do some heavy lifting, some murdering and being murdered, is the ever-versatile Elizabeth Moss, playing both Kitty Tyler and tether mother, Dahlia. As with the redoubtable Ms. Nyong'o, Ms. Moss manages to lend Us some temporary authority.

|

| I knew white carpet was a bad idea! Moss on Moss violence in Us. |

A shame, because some of Mr. Peele's ideas, some of his images, do seem rich with possibility. With Get Out, he created a film of mainstream appeal in which thorny issues of race were not only front and center, but focused less on blatant racism than sinister appropriation, instances of which almost never enter the discourse of popular culture.

A shame, because some of Mr. Peele's ideas, some of his images, do seem rich with possibility. With Get Out, he created a film of mainstream appeal in which thorny issues of race were not only front and center, but focused less on blatant racism than sinister appropriation, instances of which almost never enter the discourse of popular culture.The obvious thing in Get Out would have been to refer somehow to common examples of white culture appropriating dress, language and music. This is somewhat true of the Tylers in Us, amusingly hoisted on that petard. When they desperately command their Siri-like device to call the police when their doppelgangers appear, the virtual assistant instead plays NWA's "Fuck Tha Police," a good bit of which we hear. In Get Out, Peele took such notions a step further with appropriations of the actual flesh and bones of African Americans and for a time married that conceit brilliantly with the framework of a horror film.

There's a moment in Us when Dahlia, the tethered one to Kitty Tyler, prowls about the house, menacing all in her path, including Adelaide. Taking a short break from the mayhem, Dahlia plays with a lipstick. Elizabeth Moss in this moment manages to convey a being both feral and child-like in her manic enjoyment of the ritual.

In such rituals, in similar matters of makeup, skin and appearance, there would seem to much potential for that deeper of level of meaning after which Us so frequently gropes but fails to grasp. There is not only the expectations placed upon women and their appearance, not simply skin colors over which people are divided, for which they're discriminated, but also the varying skin tones by which African Americans are judged and sometimes divided, from within and without. Lupita Nyong'o has spoken on the latter topic with some eloquence. But in Us, it's just another lost opportunity.

As Us stumbles into it's silly, subterranean climax, the problem isn't just a complete lack of logic, it's a film that can't even succeed on it's supposedly scary surface. Last year's Mandy from director Panos Cosmatos was not exactly a masterpiece. It became even more ludicrous as it tried to explain things...like its demon bikers for instance. While story is apparently not Mr. Cosmatos' strong suit, Mandy held one's attention to the gory end, thanks in part to the director's vivid, feverish visual sense and a classically wack performance from Nicolas Cage. With Us, we're left with only a lot

of half-baked allegory and a final helicopter shot of red-suited doppelgangers inexplicably reenacting Hands Across America. Watch out for those wildfires, oh tethered ones! The real California can be much more scary than anything dreamed up in this film.

The only clear moral of the story here seems to be that when visiting those boardwalk or pier carnivals, those charming old attractions, best that we confine ourselves to the well-lighted midways, best to keep the little ones safe from the siren song of the mysterious fortune telling machine, the ominous fun house. How about a nice game of skee ball? Perhaps some Whac-A-Mole? That might be the best thing for all of us.

|

| And yet, it could have been far worse. The doppelgangers might have decided to favor us with their own version of "We Are the World." The horror! |

db

Comments

Post a Comment