What-ho! Yorgos Lanthimos down some dark, rich, reimagined corridor of English history? The Greek filmmaker has generally confined himself to the relative present. Much as he has charted out unique little worlds in his films beyond the obvious grasp of time or place, each has occurred in an astringently modern setting. You know - cars, electricity and whatnot.

|

| Alps (2011) |

|

| Dogtooth (2009) |

The absurdity, the excess...the general fucked-upness of this rarefied world is made obvious enough in the initial scenes of The Favourite. Early on there is a race. Of ducks. A pack of howling aristocrats, beneath their ample wigs and rich furnishings root fervently as favorite ducks scamper over a makeshift race course on a hardwood floor. This while the country is at war with France and countless citizens are suffering, no doubt, various privations. What may well be cinema's first-ever duck race, Lanthimos captures in a slow-motion, duck-level point of view.

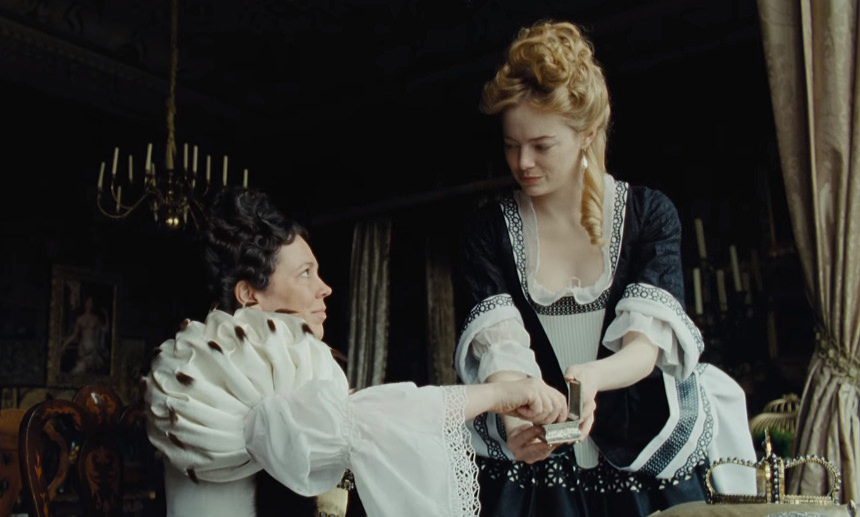

Earlier, we had seen Queen Anne take a blindfolded Sarah Churchill (Yes, that Churchill family; the cigar-chomping Winston was a descendant), Duchess of Malborough into a room where was displayed an impressive model of a palace the Queen planned to have built for her then-favourite. This, Blenheim Palace, the home to Churchills for generations. Lady Malborough demurs with flimsy vehemence and we find out just how attuned is this monarch to the affairs of state:

"My dearest Queen - you are mad! Giving me a palace. It is a monstrous extravagance. Mrs. Morley, we are at war."

"We won."

"Oh no, it is not over. We must continue."

"Oh. I did not know that."

Pronouncing those last, sharply clipped syllables is Olivia Coleman, presiding for the second time in a Lanthimos film. In The Lobster, she was the manager of the very unique hotel where guests either find a romantic partner or are turned into an animal of choice. With The Favourite, the delightful Coleman has gotten a major promotion to queen. It's a rich role in a film where there are three juicy parts for the women in leading roles.

And yet, the queen business is not all glamour, or even mainly glamour, as The Favourite would lead us to believe. One of the first occasions we see Queen Anne is in the fairly harsh appraisal of a profile shot, flesh of the neck and face already beginning to give up the fight. In a story in which we're witness to most every unattractive facet of the English sovereign, there's no more humbling interlude than when we see Anne greedily consuming sweets, only to vomit in turn, her face wearing remnants of the full cycle.

This queen is beset with a billowing sadness in addition to several physical maladies. We see her at times rage like a mad woman. At one theatrical moment of desperation she perches in an opened window a few floors above the ground, clearly waiting though she is to be talked down, which Lady Malborough does in her peremptory way, jerking the queen unceremoniously back onto the bedroom floor.

There's no more eloquent expression of Anne's miserable sense of isolation than when she's wheeled into a richly-appointed chamber at some point between dinner and post-dinner entertainment. She first observes with with some pleasure Lady Malborough involved in a comically elaborate dance with a man of the court. Already powdered and painted like a kabuki doll, the royal mien slowly sets into the deep sadness for which it seems to have been prepared. Coleman accomplishes this without seeming movement, the dark eyes glistening with tears, that mask almost imperceptibly hardening into desolation.

And yet, through the procession of the film's eight sections or chapters (With titles like, "This Mud Stinks," "I Do Fear Confusion and Accidents," "I Dreamt I Stabbed You in the Eye," etc.) we do get a fuller portrait of this queen and a display of Ms. Coleman's formidable talent.

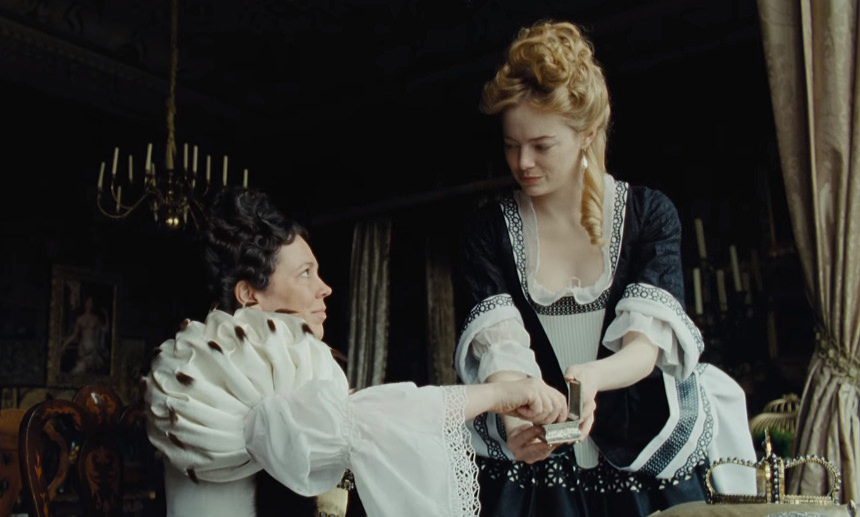

Perhaps no where else does Anne seem simply a human being at her ease than in a scene where she speaks of her 17 rabbits to servant on the rise, Abigail, a cousin of Lady Malborough who had lost all standing in the world prior to her arrival (coated with that stinking mud to which the chapter heading alluded) at the queen's residence.

As it turns out, the rabbits are surrogate children, the number significant, matching the pregnancies that Anne had undergone without producing an heir (The rabbits might be a fancy of the script of Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara, but the unfortunate Queen Anne did apparently survive 17 such reproductive ordeals). Although the queen first rebuffs the servant as an unsuitable substitute for her favourite, she warms to a kind of happiness as the calculating Abigail takes an interest in the furry ersatz royal children scampering about. Here a bit of sun and warmth in the generally harsh climate in which this queen exists. Also an indication that Coleman could merely charm us for two hours if she or the film had no grander ambitions.

Playing Abigail, a woman with a kind of Scarlett O'Hara "As God is my witness," purpose (veiled though it may be) is Emma Stone. To see Ms. Stone in a worthy role at this point in her career is like seeing a firework approaching the apex of its flight against a dark curtain of sky: brilliant, impossible not to gaze upon...rather life-affirming. And with this Abigail, eventually elevated by the queen back into the ranks of the peerage as the Duchess Masham, Emma Stone has stepped into a very worth role.

We are witness to some of the indignities of this woman fallen well below her born station: before he pushes her unceremoniously into that stinking mud a fellow passenger in the coach carrying Abigail to the royal residence first leers at her and then proceeds to pleasure himself before all riding in the small enclosure (and you thought your last ride on the bus or subway was a trial...); a fellow servant gives her a bucket with which to clean a floor without mentioning that Abigail's bare hands will be plunged into burning lye; and for the presumption of fashioning a poultice out of gathered herbs to soothe the Queen's gout-afflicted legs, she's whipped, before the sentence is commuted, as it were, when it's found the treatment actually works.

Trials indeed. None of which perhaps compare to being a young woman lost by her father in a game of whist. That episode Abigail recounts in typically matter of fact fashion, "The debt was to a balloon-shaped German man with a thin cock. Thankfully, I manged to convince him a woman has her blood 28 days a month." Abigail gains favor not only because of her skill as an amateur apothecary, but because Lady Malborough recalls that profligate father, who ultimately perished in a fire of his own setting, with some fondness. "I liked your father. He had charm to burn. Then I guess he did."

Canny though she is, Lady Malborough has a rival for the queen's affections before she quite realizes it. Just as Abigail's rifle shooting improves - we see two telling intervals with she and Lady Malborough blasting flung pigeons for target practice - so does her focus on the ultimate court prize.

Canny though she is, Lady Malborough has a rival for the queen's affections before she quite realizes it. Just as Abigail's rifle shooting improves - we see two telling intervals with she and Lady Malborough blasting flung pigeons for target practice - so does her focus on the ultimate court prize.

Being the queen's favourite in this fictional court means not only wielding political influence and being a beneficiary of the monarch's largesse (you know, your own palace, that sort of thing), but sharing the royal bed. Typical of any Lanthimos film and particular to this screenplay originally written by Ms. Davis and worked over by Mr. McNamara (and possibly the director himself), the sexual triangle is more frank possibility than salacious plot device. It's a rare story of power in which men are relegated to secondary positions of influence by a barrier of female sexuality and alliance. And yet, since this is still all happening on planet Earth and within the English aristocracy, each woman is subject to her own rules of gravity.

The formidable Lady Malborough gets a very clear indication that the tide has turned when she creeps into the royal bedchamber one evening and discovers Abigail has usurped her in the queen's bed and affection. The upstart having come up (or down) in the world by not so accidentally falling asleep while the queen was away. When Anne returns to her chamber and naturally calls out this egregious bit of presumption, Abigail has to flee the bed, and Ms. Stone as the upwardly-mobile Abigail looks like a golden-haired figure from Botticelli, emerging not from a giant scallop but from the covers of the queen's four-poster bed. Come night, memories of that young flesh still fresh in the queen's mind, Abigail is summoned, ostensibly to minister to the queen's ailing legs, but, of course...

This whole, strange world unto itself Lanthimos and cinematographer Robbie Ryan capture often in guttering natural (i.e., candle) light, all the better to throw dubious goings on into appropriate gradations of shadow. Ms. Stone, in keeping with the relative shapeshifting of her character, has her very eye color and skin tone rendered in strongly contrasting shades from one scene to another. At times, a wide-angle lens is utilized, not technically a fisheye, but one that lends the same broad, slightly distorted perspective. Cast as it is upon this world, the implication is clear: what is really more distorted, the perspective or the scene itself?

Consistent with both the sumptuousness and existential rot of the royal court, The Favourite's soundtrack features both the rich salvos of Baroque music one might expect, as well as well as a spare score by Komeil Hosseini. As the intrigue and the general madness ensue, there are solitary plinkings of keyboard, nervous plucks of stringed instrument, altogether like a dark night of the soul of some troubled chamber orchestra or quartet.

As with Olivia Colman, Rachel Weisz has found herself very much at home in the films of Yorgos Lanthimos. Weisz is at her best playing to richly shaded extremes of sweetness or malice, something far more interesting than any sort of dreary virgin/whore dichotomy.

As with Olivia Colman, Rachel Weisz has found herself very much at home in the films of Yorgos Lanthimos. Weisz is at her best playing to richly shaded extremes of sweetness or malice, something far more interesting than any sort of dreary virgin/whore dichotomy.

The woman actually makes goodness (think of her work in The Lobster, or Rian Johnson's The Brothers Bloom) appealing in a way that doesn't necessitate a prior lobotomy. And yet this same actor is entirely believable inhabiting characters whose ire should be avoided at all cost. Abigail realizes she's provoked that ire when she walks into the library one morning and Lady Malborough begins to hurl books at her ("Did you see the book of poetry from the Dryden fellow" - fling!). When Ms. Weisz subsequently utters the line, "If you do not go, I will start kicking you and I will not stop," Abigail believes her and so do we.

In the film and among the complex trio of women at its center, Lady Malborough is perhaps the most transgressive character in terms of behavior and dress. But even she exists on high perch of favor only as long as her monarch wishes it so. The shrewd and brazen Abigail manages to send Lady Malborough toppling and solidifies her place at court. But lest she forget herself, the ailing queen grabs her hair near film's end and forces her to minister the ever-troublesome royal legs.

Abigail might be the least sincere of the three women, but it's to the credit of the screenplay and Emma Stone that her likely calculated moments of candor and humility, offered along the way to Lady Malborough and Queen Anne, don't seem entirely false. What's clear in the scenes subsequent to Lady Malborough's banishment from court is that what might be left of Abigail's soul is succumbing to that rich and rotting atmosphere of court.

As for the queen, expressed in a brilliant final montage, she is buffeted by piercing and conflicting demands of monarchy, womanhood, mortality, loss, etc. How to find any identity and peace in such a such maelstrom, in such rarefied air? Fare thee well, struggling queen. As you were, Mr. Lanthimos.

And yet, the queen business is not all glamour, or even mainly glamour, as The Favourite would lead us to believe. One of the first occasions we see Queen Anne is in the fairly harsh appraisal of a profile shot, flesh of the neck and face already beginning to give up the fight. In a story in which we're witness to most every unattractive facet of the English sovereign, there's no more humbling interlude than when we see Anne greedily consuming sweets, only to vomit in turn, her face wearing remnants of the full cycle.

This queen is beset with a billowing sadness in addition to several physical maladies. We see her at times rage like a mad woman. At one theatrical moment of desperation she perches in an opened window a few floors above the ground, clearly waiting though she is to be talked down, which Lady Malborough does in her peremptory way, jerking the queen unceremoniously back onto the bedroom floor.

There's no more eloquent expression of Anne's miserable sense of isolation than when she's wheeled into a richly-appointed chamber at some point between dinner and post-dinner entertainment. She first observes with with some pleasure Lady Malborough involved in a comically elaborate dance with a man of the court. Already powdered and painted like a kabuki doll, the royal mien slowly sets into the deep sadness for which it seems to have been prepared. Coleman accomplishes this without seeming movement, the dark eyes glistening with tears, that mask almost imperceptibly hardening into desolation.

And yet, through the procession of the film's eight sections or chapters (With titles like, "This Mud Stinks," "I Do Fear Confusion and Accidents," "I Dreamt I Stabbed You in the Eye," etc.) we do get a fuller portrait of this queen and a display of Ms. Coleman's formidable talent.

Perhaps no where else does Anne seem simply a human being at her ease than in a scene where she speaks of her 17 rabbits to servant on the rise, Abigail, a cousin of Lady Malborough who had lost all standing in the world prior to her arrival (coated with that stinking mud to which the chapter heading alluded) at the queen's residence.

As it turns out, the rabbits are surrogate children, the number significant, matching the pregnancies that Anne had undergone without producing an heir (The rabbits might be a fancy of the script of Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara, but the unfortunate Queen Anne did apparently survive 17 such reproductive ordeals). Although the queen first rebuffs the servant as an unsuitable substitute for her favourite, she warms to a kind of happiness as the calculating Abigail takes an interest in the furry ersatz royal children scampering about. Here a bit of sun and warmth in the generally harsh climate in which this queen exists. Also an indication that Coleman could merely charm us for two hours if she or the film had no grander ambitions.

Playing Abigail, a woman with a kind of Scarlett O'Hara "As God is my witness," purpose (veiled though it may be) is Emma Stone. To see Ms. Stone in a worthy role at this point in her career is like seeing a firework approaching the apex of its flight against a dark curtain of sky: brilliant, impossible not to gaze upon...rather life-affirming. And with this Abigail, eventually elevated by the queen back into the ranks of the peerage as the Duchess Masham, Emma Stone has stepped into a very worth role.

We are witness to some of the indignities of this woman fallen well below her born station: before he pushes her unceremoniously into that stinking mud a fellow passenger in the coach carrying Abigail to the royal residence first leers at her and then proceeds to pleasure himself before all riding in the small enclosure (and you thought your last ride on the bus or subway was a trial...); a fellow servant gives her a bucket with which to clean a floor without mentioning that Abigail's bare hands will be plunged into burning lye; and for the presumption of fashioning a poultice out of gathered herbs to soothe the Queen's gout-afflicted legs, she's whipped, before the sentence is commuted, as it were, when it's found the treatment actually works.

Trials indeed. None of which perhaps compare to being a young woman lost by her father in a game of whist. That episode Abigail recounts in typically matter of fact fashion, "The debt was to a balloon-shaped German man with a thin cock. Thankfully, I manged to convince him a woman has her blood 28 days a month." Abigail gains favor not only because of her skill as an amateur apothecary, but because Lady Malborough recalls that profligate father, who ultimately perished in a fire of his own setting, with some fondness. "I liked your father. He had charm to burn. Then I guess he did."

Canny though she is, Lady Malborough has a rival for the queen's affections before she quite realizes it. Just as Abigail's rifle shooting improves - we see two telling intervals with she and Lady Malborough blasting flung pigeons for target practice - so does her focus on the ultimate court prize.

Canny though she is, Lady Malborough has a rival for the queen's affections before she quite realizes it. Just as Abigail's rifle shooting improves - we see two telling intervals with she and Lady Malborough blasting flung pigeons for target practice - so does her focus on the ultimate court prize.Being the queen's favourite in this fictional court means not only wielding political influence and being a beneficiary of the monarch's largesse (you know, your own palace, that sort of thing), but sharing the royal bed. Typical of any Lanthimos film and particular to this screenplay originally written by Ms. Davis and worked over by Mr. McNamara (and possibly the director himself), the sexual triangle is more frank possibility than salacious plot device. It's a rare story of power in which men are relegated to secondary positions of influence by a barrier of female sexuality and alliance. And yet, since this is still all happening on planet Earth and within the English aristocracy, each woman is subject to her own rules of gravity.

The formidable Lady Malborough gets a very clear indication that the tide has turned when she creeps into the royal bedchamber one evening and discovers Abigail has usurped her in the queen's bed and affection. The upstart having come up (or down) in the world by not so accidentally falling asleep while the queen was away. When Anne returns to her chamber and naturally calls out this egregious bit of presumption, Abigail has to flee the bed, and Ms. Stone as the upwardly-mobile Abigail looks like a golden-haired figure from Botticelli, emerging not from a giant scallop but from the covers of the queen's four-poster bed. Come night, memories of that young flesh still fresh in the queen's mind, Abigail is summoned, ostensibly to minister to the queen's ailing legs, but, of course...

This whole, strange world unto itself Lanthimos and cinematographer Robbie Ryan capture often in guttering natural (i.e., candle) light, all the better to throw dubious goings on into appropriate gradations of shadow. Ms. Stone, in keeping with the relative shapeshifting of her character, has her very eye color and skin tone rendered in strongly contrasting shades from one scene to another. At times, a wide-angle lens is utilized, not technically a fisheye, but one that lends the same broad, slightly distorted perspective. Cast as it is upon this world, the implication is clear: what is really more distorted, the perspective or the scene itself?

Consistent with both the sumptuousness and existential rot of the royal court, The Favourite's soundtrack features both the rich salvos of Baroque music one might expect, as well as well as a spare score by Komeil Hosseini. As the intrigue and the general madness ensue, there are solitary plinkings of keyboard, nervous plucks of stringed instrument, altogether like a dark night of the soul of some troubled chamber orchestra or quartet.

The woman actually makes goodness (think of her work in The Lobster, or Rian Johnson's The Brothers Bloom) appealing in a way that doesn't necessitate a prior lobotomy. And yet this same actor is entirely believable inhabiting characters whose ire should be avoided at all cost. Abigail realizes she's provoked that ire when she walks into the library one morning and Lady Malborough begins to hurl books at her ("Did you see the book of poetry from the Dryden fellow" - fling!). When Ms. Weisz subsequently utters the line, "If you do not go, I will start kicking you and I will not stop," Abigail believes her and so do we.

In the film and among the complex trio of women at its center, Lady Malborough is perhaps the most transgressive character in terms of behavior and dress. But even she exists on high perch of favor only as long as her monarch wishes it so. The shrewd and brazen Abigail manages to send Lady Malborough toppling and solidifies her place at court. But lest she forget herself, the ailing queen grabs her hair near film's end and forces her to minister the ever-troublesome royal legs.

Abigail might be the least sincere of the three women, but it's to the credit of the screenplay and Emma Stone that her likely calculated moments of candor and humility, offered along the way to Lady Malborough and Queen Anne, don't seem entirely false. What's clear in the scenes subsequent to Lady Malborough's banishment from court is that what might be left of Abigail's soul is succumbing to that rich and rotting atmosphere of court.

As for the queen, expressed in a brilliant final montage, she is buffeted by piercing and conflicting demands of monarchy, womanhood, mortality, loss, etc. How to find any identity and peace in such a such maelstrom, in such rarefied air? Fare thee well, struggling queen. As you were, Mr. Lanthimos.

db

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62375133/favourite11.0.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment