Only late in the proceedings of writer/director Tom McCarthy's masterful Spotlight, not long before the two-hour mark of the 129-minute film, does a character really raise their voice. Only shortly thereafter does the director make what could be construed as his first rhetorical flourish. Given the drama inherent in Spotlight, that restraint is particularly admirable. The sexual abuse of children on the part of Roman Catholic priests in the Boston Archdiocese as revealed and conveyed by reporters of the Boston Globe could hardly have been more damning, more outrageous. The material could hardly be more dramatic. And yet, a story that would seem to require the dimensions of opera is handled like a precise, heartbreaking piece of chamber music by McCarthy and his uniformly excellent cast.

Sounding beneath Spotlight's slowly-building theme genuine tragedy - we're reminded prior to the closing credits that this was and is a global phenomenon - is an unadorned refrain, lightly cloaked in the colors of elegy, for the love of print journalism in general and the work of the Boston Globe in particular. The film takes its name from the Spotlight team of The Globe, the longest continuously-operating investigative unit among American newspapers.

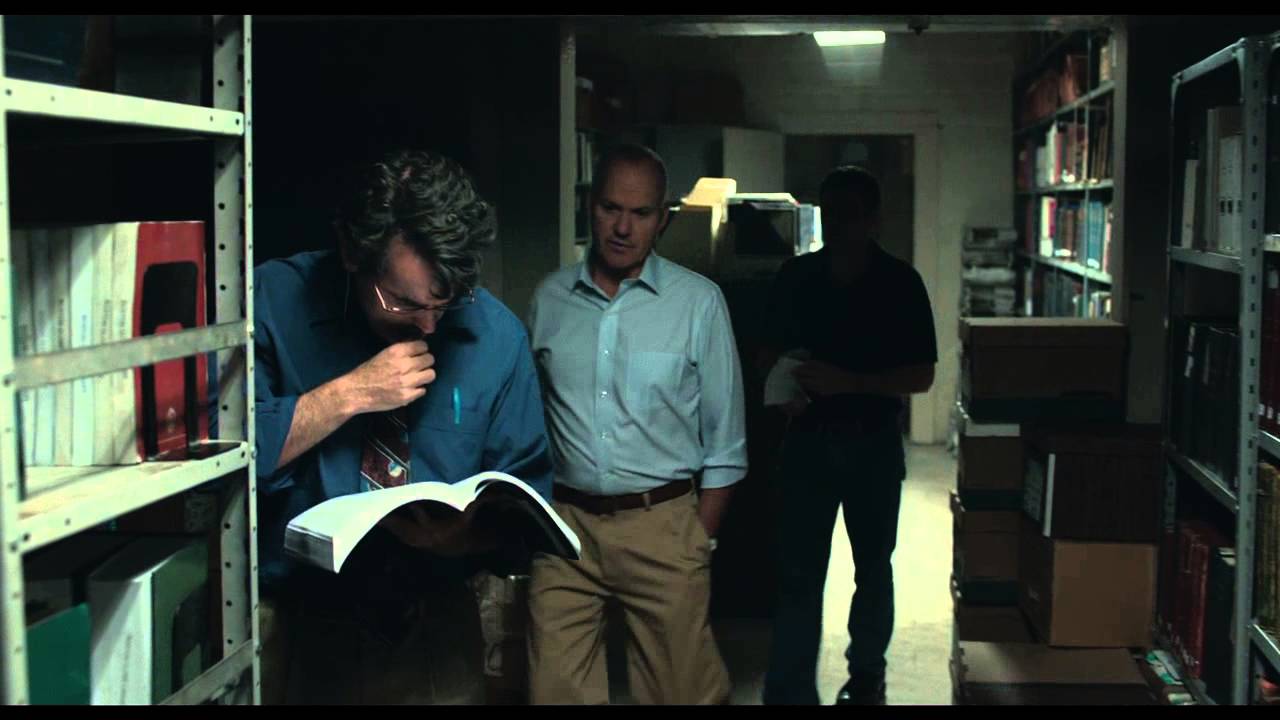

Spotlight grounds itself not only in the process of print journalism, but the particular place where its writers work, hover, to which they seem to drift more naturally than their actual homes. We see not only the warrens of cubicles and other blandly-paletted work spaces, but stairwells, a garage area shortcut between offices, a staff lounge the size of a modest walk-in closet. When Spotlight reporter Matt Carroll (Brian d'Arcy James) is joined by his chief, Walter Robinson (Michael Keaton) and the paper's assistant managing editor, Ben Bradlee, Jr. (John Slattery) in a poorly-lit, dungeon of a basement storage room (which does somewhat miraculously offer cell phone reception) where they examine Catholic Church directories, Bradlee asks, "What's that smell?" "There's a dead rat in the corner," Caroll notes matter-of-factly. Given the foul nature of the developing story, the rodent would also seem to be redolent of metaphor or threat from the powerful organization that is being confronted. But no, it's just a dead rat in corner. Not a lot of glamour in this newspaper business. All of this might look eerily familiar to those who labored in the Globe offices some 15 years ago, but the vast majority of Spotlight's shooting was done on set in a former Sears department store in Toronto, the ace work of set designer William Cheng and his team impressively recreating the Boston offices circa 2001.

There's also a sense of surrogate family, occurring sometimes to the detriment reporters non-work relationships. After that one confrontation late in Spotlight that involves reporter Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) screaming "This is bullshit!" at boss "Robby" Robinson when he won't run story as is, the upset Rezendes later rings the doorbell of fellow Spotlight reporter Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams). "Tough day at work, Mike?" asks Pfeiffer's husband as he opens the door with obvious chagrin, the man clearly accustomed to his wife's work following her home, if not always in corporeal form.

It's a kind of family gathering that occurs in the film's second scene, as Bradlee and Robinson speak in honor of a departing colleague in their typically understated fashion. There is also a joke about the paper's incoming editor and whether the retiring writer knows something that everyone else doesn't.

It is the the arrival of the new editor, Marty Baron that sets the Boston Globe in pursuit of the story of abusive priests and ultimately on a collision course with perhaps that most revered - at least in the top two or three; depending on how the locals are feeling about the Red Sox - of Boston institutions, the Catholic Church. As the outsider Baron, it is the voice himself, Liev Schreiber. If you've watched many documentaries on HBO or PBS in the past decade, you have no doubt heard Mr. Schreiber's voice a good deal. That carefully-modulated baritone goes some way toward exemplifying the tone of performances in Spotlight, just as Baron pilots the Globe calmly, but doggedly into what will be a much bigger story than anyone imagines.

It is the the arrival of the new editor, Marty Baron that sets the Boston Globe in pursuit of the story of abusive priests and ultimately on a collision course with perhaps that most revered - at least in the top two or three; depending on how the locals are feeling about the Red Sox - of Boston institutions, the Catholic Church. As the outsider Baron, it is the voice himself, Liev Schreiber. If you've watched many documentaries on HBO or PBS in the past decade, you have no doubt heard Mr. Schreiber's voice a good deal. That carefully-modulated baritone goes some way toward exemplifying the tone of performances in Spotlight, just as Baron pilots the Globe calmly, but doggedly into what will be a much bigger story than anyone imagines.Tom McCarthy was an actor for some years before he became a writer and director of films. In all of his films (I've not seen the almost inexplicable Adam Sandler vehicle The Cobbler, which McCarthy might prefer to leave off his CV), that acting experience shows. He writes rich roles for his actors and obviously creates an environment in which they are at ease to their best, most unencumbered work. Throughout Spotlight's redoubtable cast there is plenty of that intelligent, understated, good work, particularly Schreiber as Baron and Stanley Tucci as Mitchell Garabedian, the attorney bringing suits against the church. There is also the ongoing and welcome resurgence of Michael Keaton as the Spotlight chief.

Perhaps the best measure of the writing (the screenplay by McCarthy and Josh Singer) and the director's way with actors is the quality of the minor roles in Spotlight. These include relatively brief but memorable performances by Paul Guilfoyle as church representative Pete Conley and Jamey Sheridan as a lawyer friend of Robby Robinson's, hired by the church to consult on abuse cases. Irishmen both, of course, Guilfoyle and Sheridan both evince the weight and privilege of the status quo in Boston. Whether speaking in friendly or more aggressive tones - much as Guilfoyle's Conley is one of those powerful men who is more likely to flatten an adversary with a smile than threat - both actors sound right. Even better, they bespeak an insider's intelligence and code of conduct without uttering a word.

Perhaps the best measure of the writing (the screenplay by McCarthy and Josh Singer) and the director's way with actors is the quality of the minor roles in Spotlight. These include relatively brief but memorable performances by Paul Guilfoyle as church representative Pete Conley and Jamey Sheridan as a lawyer friend of Robby Robinson's, hired by the church to consult on abuse cases. Irishmen both, of course, Guilfoyle and Sheridan both evince the weight and privilege of the status quo in Boston. Whether speaking in friendly or more aggressive tones - much as Guilfoyle's Conley is one of those powerful men who is more likely to flatten an adversary with a smile than threat - both actors sound right. Even better, they bespeak an insider's intelligence and code of conduct without uttering a word. The same goes for the characters on whom all of that power descends, the victims of the abuse. Much as the larger story, as Marty Baron insists to his reporters, is the systemic abuse and cover-up, the fact that Cardinal Law and those even higher up in the church were aware of the problem, McCarthy, as ever, lets any larger themes be ground in personal stories. Appearing only once or twice on screen we see full, memorable turns from Joe Crowley and Patrick McSorely (the first client Garabedian allows to be interviewed) as men just emerging or still struggling with substance abuse decades after their violation by priests. Victims certainly, but in just a few minutes we get some sense of the fuller person.

The victim who serves as the most vocal catalyst for making the story public is Phil Saviano (Neal Huff). Dismissed by Bradlee as a crackpot they had interviewed years earlier, Saviano is a man that has told his story so often that it's like a book with dog-eared pages and underlined passages. He arrives with a banker's box of information and begins by pulling out a picture that bears his name and age (9) at the time of his initial abuse. Saviano's obvious exasperation at year's of indifference on the part of the press nearly renders him the unreliable fringe dweller that Bradlee is inclined to label him, a sobering reminder that if you abuse a person or people thoroughly enough, they come to be considered, even by themselves in some cases, unworthy of consideration or compassion. The writing of McCarthy and Singer and the barely-bottled intensity of Huff manage to convey this exasperation almost telegraphically while avoiding the obvious pitfall of too much, too much. So, wisely, goes the film.

The use of Richard Jenkins own distinct and authoritative baritone it typical of McCarthy's quietly skillful direction. The scenes in which Rezendes speaks to Sipe while alone in his apartment carry a tension and gravity that wouldn't quite be the case with a more standard interview scene. During their first conversation, Sipe explains that sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests is so widespread and long-established that it's a "a recognizable psychiatric phenomenon."

McCarthy and Singer do employ one obvious touch of storycraft in their otherwise seamless narrative. This something of a red herring in the form a Globe staffer having known about more widespread abuse years before the 2001 Spotlight work. Phil Saviano explains to the Spotlight team that he had sent in an entire box of evidence to the newspaper back in the 90's. Given that Ben Bradlee seems intent on dimissing Saviano and tries to discourage the story's development, he certainly seems like the best candidate for the person who quashed the story.

Ultimately, the point isn't who at the Globe sat on the damning information. More a matter of the "How could you?" getting turned on all parties. The villainy might be clear enough in the overall story, but the tacit assistance of many, including the press, allowed the tragedy to find a greater breadth and duration. Or as Garabedian says to Rezendes during a dinner conversation, "If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one."

Garabedian's play on the Hilary Clinton book title speaks to both Spotlight's moral complexity and its deft shading of character. The quip perfectly expresses the attorney's righteousness as well as his sense of self-importance. Earlier in the conversation with Rezendes as the two men discussed relationships, Garabedian had said that his decision to stay single was a conscious one. "My work is too important," he says, drawing a slight smile from the Globe reporter.

Garabedian's play on the Hilary Clinton book title speaks to both Spotlight's moral complexity and its deft shading of character. The quip perfectly expresses the attorney's righteousness as well as his sense of self-importance. Earlier in the conversation with Rezendes as the two men discussed relationships, Garabedian had said that his decision to stay single was a conscious one. "My work is too important," he says, drawing a slight smile from the Globe reporter. As the Spotlight teams purses the story and applies increasing pressure - "You want to be on the right side of this" is uttered more than once - to its sources, they find the moral indignation turned back on them several times. This is the case with attorney Eric Macleigh (Billy Crudup). When Robinson rightfully points out that Macleish has made a cottage industry out of representing the families of abused children - getting them a nominal settlement and an acknowledgement of guilt in exchange for their silence - the lawyer ultimately tells him (and Sacha Pfeiffer) that he sent a list of 20 abusive priests to the Globe in the 90s. "Check your clips, Walter," are Macleish's final words. Similarly, Robinson's old friend, Jim Sullivan (Sheridan) asks him where the Globe had been all the intervening years while the abuse was going on and attempts were made to make the story public. Sheridan is the one church insider the paper needs to confirm the scope of the abuse in Boston before they can run the story. After kicking him out of his house and then following him out to the street to confront Robinson (and his paper) on his hypocrisy, Sullivan asks to see the list that Robinson practically brandished after being invited into his old friend's house prior to Christmas 2001. Sheridan quickly scans the two pages listing the names of 77 priests, asks for a pen and then makes large circles on each page - he implicates every one of the listed priests; all of the names.

So go the confrontations in Spotlight. If they're fights, no one walks away unbloodied. But really, there is mainly a sobering, encompassing truth that leaves no one in the mood to feel too good about themselves. Even before the Spotlight reporters (along with Bradlee and Barron) realize their culpability in not telling the story sooner, there is virtually nothing in the way of chest thumping as they ready themselves to investigate the story, to basically take on the Catholic Church. Instead of bravado, we see a kind of kind of wary determination, a resigned gulp. Robinson and Rezendes find themselves in the Spotlight office one Sunday morning. Rezendes asks his boss if their new editor knows what he's up against. No, Robinson says, but he doesn't think Barron is likely to be deterred. Rezendes says he thinks that's refreshing. "Unless he's wrong," says Robinson and both men have one of those quiet moments, considering everything that's at stake, including their careers.

Those moments between the staffers at the Globe, particularly the Spotlight unit, do bespeak a kind of familial intimacy, for the good and the sometimes irritating. When Robinson urges Rezendes to keep after the elusive Garagedian, Rezendes says, "He's a pain in the ass." "You can be a pain the ass," rejoins his boss. Sacha Pfeffer, sitting nearby, offers a confirming "Mmm" without looking up from her work.

That intimacy of performance and exchange is captured and mirrored by McCarthy's direction and the work of his cinematographer, Masanobu Takayangi. The photography is close and steady, usually an unobtrusive observer in one room or another. One of the few intervals of conscious movement occurs when Matt Carroll realizes that one of the sites used by the church to house priests that have been pulled from parishes where they have violated children is just around the corner from his home and children. The camera follows him as he bursts out the door of his house and stalks to the inconspicuous church-owned building nearby, staring at the house in the midst of a neighborhood full of children. Otherwise, Takayangi keeps the perspective limited, only occasionally pulling back to appropriately reveal a church looming over a playground or court building.

The scope of the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church is obvious enough in its tragic breadth. So too the reprehensible conduct of priests who became sex offenders and the church officials who protected and even enabled them. In his version of the story we see in Spotlight, written with Josh Singer, with the restraint of his direction, Tom McCarthy avoids the very obvious pitfall of trundling out the rusty scapegoat mechanism. The focus, when not personal, is admirably reflexive. Only at film's end, when those aforementioned flare-ups of shouting and rhetoric finally occur, they seem earned. Sometime after Rezendes blows up at Robinson in the Spotlight office, we hear a children's choir singing "Silent Night." Eventually we see the choir of young singers at a holiday service. Rezendes stands at the back of the church, an apt symbol of a man who will probably never get back to his faith. As the camera scans the children in the choir, the story is returned to its rightful place.

On the morning when expose is finally published early in 2002, the director gives us the first broad perspective on the city where all of this sad business has taken place. It's a shot of Boston from the harbor as if a bomb was about to fall. Which, of course, it was.

One of the shots of the actual Boston Globe offices in Spotlight is a seemingly insignificant view of a a parking lot with an AOL (remember them?) billboard looming just beyond its periphery. Here perhaps that undercurrent of elegy for actual journalism overrun the by the fucked-up democracy of unmediated digital information. The shots of those clips - old news clippings in form of yellowing paper issues and cut-out stories, microfilm, digital archives, etc. - being pulled and photocopied, of a cart of files rumbling inexorably down a hallway, of presses running, seem more than mere nostalgia, more than the conventions of newspaper films. There's a kind of celebration of process here. Of working to get to some greater truth or understanding, difficult as it might be to face for all involved. With Spotlight, McCarthy also provides a celebration of the process and collaboration of filmmaking - methodical, focused, no less deeply-felt, no less compelling in its art and story for its restraint.

Comments

Post a Comment