"I'll soon take off my funny disguise....And once you see what's underneath...you're going to wish you were dead!" And hello to you, too! The rather dire warning comes from "Mr. Babadook" through the agency of a very persistent children's book that bears name of the monster. Thus, The Babadook, writer and director Jennifer Kent's creepy and assured feature film debut. Is the Babadook real? Merely a projection, a top-hatted fiend from a children's book that sets off a couple of already febrile minds? Or perhaps...we have seen the monster and it is us?

Ms. Kent demonstrates a very sure hand and supple knowledge of film history, the latter manifesting itself in the action of The Babadook, the film's set design and a particular channel to which the television of Amelia Vannick (Essie Davis) seems permanently tuned, showing everything from the fantastical early cinema of George Melies to the more colorful exploits of Italian horror master Mario Bava. One film that does not appear for Amelia's troubled t.v. viewing could readily express the unsettling issue at the core of The Babadook. This When A Stranger Calls (1979) and its now immortal line, "It's coming from inside the house!" Quickly establishing herself as an intrepid and knowing explorer of dark places, Jennifer Kent understands that the most frightening spaces are often found within our troubled beings, the dusty, dark corridors of the mind.

To say the very least, Amelia Vannick is having a hard time. She might be nearly seven years removed from an auto accident which resulted in the decapitation her husband, driving the couple to the hospital for the delivery of their son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), but life for the single mother and son would seem to be getting worse instead of better. Young Samuel, cute and wide-eyed though he may be when flouncing about in his spangly magician's cape and gloves, is increasingly fractious. Like many a child, he worries about monsters lurking beneath his bed, in his closet. But our Samuel is a problem solver. He invents weapons to battle his bogeyman if and when it should appear, the most impressive of which is a shoulder-mounted catapult, sort of a kiddie rocket launcher. Samuel's flair for ballistics and obsessive train of thought make him equally unpopular with exasperated school officials, disturbed relations and his own increasingly worn out mother.

To say the very least, Amelia Vannick is having a hard time. She might be nearly seven years removed from an auto accident which resulted in the decapitation her husband, driving the couple to the hospital for the delivery of their son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), but life for the single mother and son would seem to be getting worse instead of better. Young Samuel, cute and wide-eyed though he may be when flouncing about in his spangly magician's cape and gloves, is increasingly fractious. Like many a child, he worries about monsters lurking beneath his bed, in his closet. But our Samuel is a problem solver. He invents weapons to battle his bogeyman if and when it should appear, the most impressive of which is a shoulder-mounted catapult, sort of a kiddie rocket launcher. Samuel's flair for ballistics and obsessive train of thought make him equally unpopular with exasperated school officials, disturbed relations and his own increasingly worn out mother. Amelia spends most of her waking hours caring for others, wrangling her cute persona non grata of a son and tending to elderly patients at the nursing home at which she's employed, wearing a pink uniform that is one of the film's few chromatic departures from its palette of deep blue, maroon and stark white. One of The Babadook's few moments of levity occur as Amelia calls a bingo game for a room of seemingly clueless patients. "Maybe someone will win this year," she despairs. Finally, she pulls a ball out of the cage and announces "Five billion. Does anyone have five billion?" The only one who notices the sarcasm is her supervisor at a side of the room, clearly not amused.

Amelia spends most of her waking hours caring for others, wrangling her cute persona non grata of a son and tending to elderly patients at the nursing home at which she's employed, wearing a pink uniform that is one of the film's few chromatic departures from its palette of deep blue, maroon and stark white. One of The Babadook's few moments of levity occur as Amelia calls a bingo game for a room of seemingly clueless patients. "Maybe someone will win this year," she despairs. Finally, she pulls a ball out of the cage and announces "Five billion. Does anyone have five billion?" The only one who notices the sarcasm is her supervisor at a side of the room, clearly not amused.

It is at her workplace that there would seem to be some potential for a little care and warmth coming back to Amelia, in the form of another nurse, Robbie (Daniel Henshall), clearly smitten with her. This budding romance, like virtually every other scrap of independent life, is blotted out by the dark cloud of Samuel and her troublesome relationship with him. We twice see Amelia stare longingly at happy couples - one on television and another sharing pleasantries in the front seat of a car parked near her in a garage - as if observing an inviting ritual completely removed from her existence and fading from memory. Even when she attempts to quiet her libido one night, Samuel bursts in upon her, unknowingly accomplishing vibrator interruptus. The poor woman cannot get a break.

The libido clamors. Loneliness chokes like an invasive species. And the ghost of her late husband and that fateful car ride continue to haunt Amelia, as the film's opening dream sequence vividly demonstrate. All of these clamant tugs on her consciousness, her sleep, her sanity. Not to mention the aching tooth in her mouth. Quite enough to threaten anyone's sanity, even without a riotously obsessive son, whose behavior runs from the merely tiresome to full-on berserk, the latter state particularly the case during a couple of car rides that Samuel takes with all the equanimity of wet cat stuffed into a carrier cage. '

The libido clamors. Loneliness chokes like an invasive species. And the ghost of her late husband and that fateful car ride continue to haunt Amelia, as the film's opening dream sequence vividly demonstrate. All of these clamant tugs on her consciousness, her sleep, her sanity. Not to mention the aching tooth in her mouth. Quite enough to threaten anyone's sanity, even without a riotously obsessive son, whose behavior runs from the merely tiresome to full-on berserk, the latter state particularly the case during a couple of car rides that Samuel takes with all the equanimity of wet cat stuffed into a carrier cage. '

Of course, what sends both mother and son round the bend is the arrival of Mr.

Babadook. Samuel pulls the tome of the same name, bound in cloth of blood red, from a book shelf for his bedtime story one evening, though neither son nor mother know whence Mister Babadook (the book itself) came. In its black and white (mainly black) rendering and equally dark theme, Mister Babadook is like Edward Gorey in a really bad mood. The ominous picture book confirms everything that young Samuel had been sensing and gives him license to freak out at home and abroad. The story also gets under the skin of mom, disturbed by the content, the reaction of her son and the fact that the book has many blank pages after its series of sinister admonishments.

Jennifer Kent gets so much right with The Babadook, beginning with this spooky children's book (an expanded version of the one seen in the film will actually be published). This extends to the name of the monster itself, at once simple and complex, bespeaking a warm babble between child and parent and some darker, percussive, intruding force. Those contradictions consistent with the film's full, flawed characters.

Mainly, Kent succeeds with her elemental storytelling and a shooting style which avoids cheap thrills and a lot of special effects. Like all good horror, The Babadook taps into primal fears, abiding human darkness. There is the child's (or adult's) basic fear of the dark and unknown. Samuel is anychild, even if a particularly trying example, clamoring for assurance that a monster will not emerge from beneath the bed or from behind a wardrobe door not long after the lights are extinguished. Ultimately, the child's fear and the mysterious book are an avenue into the film's real darkness: what's happening to Samuel's mother Amelia.

After the initial reading of the book, the idea of the Babadook begins to trouble the mother almost as much as the son. As the monster begins to "dook-dook-dook" at the doors of her house, make its apparent initial appearances, Kent's touch as writer and director is measured, searing. Like much about her story, she go goes right to ageless basics, but presents them in a chilling relief that seems new and all her own.

After the initial reading of the book, the idea of the Babadook begins to trouble the mother almost as much as the son. As the monster begins to "dook-dook-dook" at the doors of her house, make its apparent initial appearances, Kent's touch as writer and director is measured, searing. Like much about her story, she go goes right to ageless basics, but presents them in a chilling relief that seems new and all her own.As Amelia begins to fear the monster as much as Samuel, we see her revert to that immemorial defense against supernatural bedroom invaders - she pulls a blanket over her head, cloaking both she and her son in the protective blindness of the covers. The camera is under the blanket as well, and we see a series of shudders on the part of Amelia followed by a light burning upon the surface of this wispy membrane of protection. As with the film's first scene - an apparent dream sequence in which a stunned Amelia is jerked around her crashing vehicle amidst a spray of glass - it's not immediately apparent what we're seeing, but both Essie Davis and Jennifer Kent make it completely arresting.

Among its many influences and points of cinematic correspondence, The Babadook does share a good bit of ground with The Shining. In both there is a parent sequestered with a child - the child more quickly open and attuned to apparent supernatural forces, the parent descending into a sleep-deprived madness. I've read one interview with Jennifer Kent in which Amelia Vannick is referred to as a combination of both Jack and Wendy Torrence from The Shining, and there's something to that. Ultimately, The Babadook has at once more heart and greater courage (or insight) to dip into far more unsettling waters than Stanley Kubrick's film, even with all the latter's blood and "redrum."

Since the book bearing its name would seem to have introduced the Babadook to her home, Amelia responds to the burgeoning menace by tearing it apart and banishing the pieces to a trash can. Alas, the door is later pounded and on the doorstep lies a patched-up and expanded version of the infernal picture book, the previously blank pages filled with images of a mother doing violence to both a child and dog. Not to mention more ominous text: "The more you deny, the stronger I get...the Babadook growing right under your skin."

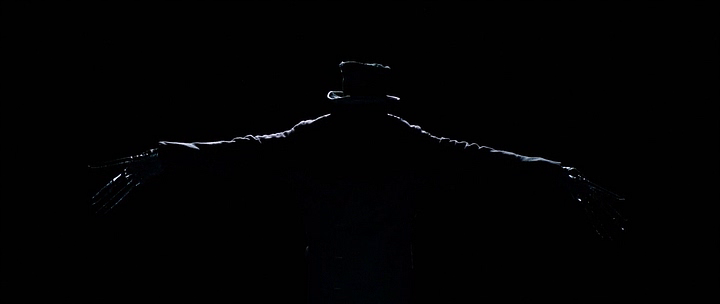

Since the book bearing its name would seem to have introduced the Babadook to her home, Amelia responds to the burgeoning menace by tearing it apart and banishing the pieces to a trash can. Alas, the door is later pounded and on the doorstep lies a patched-up and expanded version of the infernal picture book, the previously blank pages filled with images of a mother doing violence to both a child and dog. Not to mention more ominous text: "The more you deny, the stronger I get...the Babadook growing right under your skin."As the horror becomes more explicit in The Babadook, Jennifer Kent eschews both the disposable thrills of CGI-laden effects scenes, as well as the more nervous camera movements that contemporary horror films sometimes adopt, that would-be documentary approach that serves as a short cut to something real and frightening. Radek Ladczuk's camera moves fluidly through the stylized home interiors of the Vannick home, whose muted colors and stark architecture and decoration reveal a hint of German Expressionism. When the monster does appear, it's never made to completely emerge from the darkness. Just the scarecrow outline and top hat. Kent and her team apparently used puppetry and some stop action photography, among other techniques, to capture the sometimes sinister sweep, sometimes staccato progress of the Babadook. As with the best horror, the best fantasy, there are hints and triggers that let mind fill in the blanks, whether Amelia Vannick's, or ours.

From retrieving and cradling her dead husband's violin like an infant, to sitting fully clothed in a tub of water - "It's nice and warm in here" - Amelia becomes more and more unhinged. All suppressed frustration with Samuel begins to find snarling, increasingly malicious expression: "If you're that hungry, why don't you go and eat shit!.... You don't know how many times I wished it was you and not him that died....Sometimes I just wanna smash your head against a brick wall until your fucking brains pop out."

None of this, of course, likely to win Amelia any laudatory statuettes come Mother's Day. But so The Babadook bravely and frankly delves into the woman's grief, loneliness (in more ways than one), frustration and mere difficulty of being a single mother. The Babadook frightens with all the fleeting glances of its titular monster. It also chills every bit as much with the taboo of a mother at wit's end with her child.

None of this, of course, likely to win Amelia any laudatory statuettes come Mother's Day. But so The Babadook bravely and frankly delves into the woman's grief, loneliness (in more ways than one), frustration and mere difficulty of being a single mother. The Babadook frightens with all the fleeting glances of its titular monster. It also chills every bit as much with the taboo of a mother at wit's end with her child.The hints are present even before unwelcome visitor with the considerable wingspan and top hat appears on the scene. Early in The Babadook, Samuel puts his arms around his mother's neck, an embrace from which she recoils. "Don't do that!" she exclaims, though it's not clear just what the offending "it" is. A somehow inappropriate gesture as Samuel's small hands clasp and almost massage her neck? Or is she merely weary of the touch and presence of her son? Her feelings are made more explicit, even if expressed from without, when Amelia quarrels with her sister, Claire (Hayley McElhinney) at her neice's birthday party. "I can't stand to be around your son, says Claire. "You can't stand being around him yourself." Or as Jennifer Kent has said in interview, "There is something monumentally troublesome with a mother who cannot or won’t love her child—it’s almost a taboo subject. And part of what makes horror special is that it deals with taboos very well....The Babadook is about somebody who can’t or won’t...."

The job of playing this harried, ultimately crazed mother falls to the very capable Essie Davis, an old acting friend of Jennifer Kent. Davis, often wide-eyed like Noah Wiseman playing her son, ranges not only between meek solicitude and outright menace, but from the child-like to rapidly-aging adult. The sleep deprived weariness and eventual madness are extremes to which Davis takes her character without any loss of credibility or feeling. So too the reversion to primal, child-like fear in facing some terrifying thing in the dark of the bedroom, or the reluctant body language she expresses when called upon to leave her bed in the safer light of day, like a child unwilling to face a school day.

Jennifer Kent frequently uses the term "in camera" in interview. She apparently means that the look and action of the film are composed and captured, as much as possible, right on the set, without an a lot of post-production tinkering for effect. It's one of the reasons the sometimes ambiguous action of The Babadook maintains its resonance, its connection to primal fears. Ms. Kent also has a clear idea what she wants in the frame, from the film's most frightening and fanciful moments to finer threads of storytelling: those dancing fragments of glass we see in the first moments of the film reappear in Amelia's soup as she and Sam sit for a dinner to maintain a semblance of normal family life; the several shots of bare tree limbs amidst power lines are answered after the film's denouement with a bough in full bloom.

|

| The most explicit of The Babadook's influences: Lon Chaney in London After Midnight. |

The influences are many with The Babadook, but the synthesis all Jennifer Kent. There are the connections to The Shining, all those horror films playing on that unusual television. There are reminders of The Exorcist as well: during one confrontation with the Babadook, Amelia and Samuel ride a shaking bed as did a possessed Linda Blair; Samuel's "Do you wanna die?" echoes Regan's "You're gonna die up there." Despite the liberal element of influence and homage, Ms. Kent does manage something all her own, a work unique and of the present that is likely to live well beyond the limited lifespan of mere pastiche. But even the references in The Babadook bespeak discrimination more than cheap plundering. One of the images that appears on Amelia's single-channel t.v. is that of Barbara Stanwyck in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers. Hardly a film to be curated with the likes of The Shining and The Exorcist, but if you know the film, as does Ms. Kent, you know that it too involves mayhem, familial strife and a woman trapped in her own life.

Old friends Jennifer Kent and Essie Davis are two women clearly unafraid of plumbing murky waters. Both manage to give full expression to Amelia Vannick's feelings, whether noble or disturbing. It doesn't hurt that director of The Babadook is a woman, moving with a combination of compassion and candor its main character from the usual position of shrieking object to three-dimensional subject. Mainly, The Babadook succeeds because Jennifer Kent is an artist of confident vision and rigorous execution.

It's been an encouraging year for horror, even if the multiplex remains oblivious, as ever, to the more refreshing currents in film. David Robert Mitchell, while dwelling more ambiguously in the past, delivered It Follows, reminding moviegoers that the waiting for the scary thing - all apologies to Tom Petty - might be the hardest part. Sustained suspense - what a concept. They only thing clearing wanting in It Follows is any sense of subtext, something its past/present dance and Detroit setting seem all too ready to provide. The Babadook derives its power from the presence of a story that frightens on its surface and echoes ominously with its deeper theme. The story's candor cuts as deeply as might that big knife wielded by Amelia Vannick (or Jack Torrence, or....) possessed by demons without or within.

If you're unconcerned with subtext, no matter. The Babadook is an intelligent film. It's also a horror film, whose household encounters with the insistent figure in the top hat might stick with you into your next few evenings of longed-for sleep. It also provides a very useful, fundamental reminder - when a monster comes knocking, pull that blanket up over your head and try to hold out until dawn.

God, I love your writing!

ReplyDeleteBut the ending...what about the ending?

ReplyDeleteThank you, Rita, much as the review seems pretty belabored to me. As for the ending, yeah. The person with whom I watched it didn't really like it. I thought it was consistent with the story, but it wasn't that big of a deal to me. I saw it in almost exclusively symbolic terms. Or maybe it would have been good to write about that as well - essentially feeding your fears to keep them under control, keeping them close - but the review is already too long-winded. You're very kind to read. Danny

ReplyDelete