Those all-too-willing participants in reality shows have wrought even more damage than is obviously the case. Of course, there is the mental toll: billions of brain cells, lonely outposts of thought surrendering to the onslaught of gleeful indignity, seemingly as many as would drown in a Pacific of bad whisky, to the likes of the Kardashians, Real Housewives of Atlanta, New York, Orange County...the pawn shop owners, the late-to-the-party celebrities...ad nauseam. All of this, presumably, to distract viewers from the pain, the loneliness, or just the oppressive banality of their lives.

Less obvious perhaps is the obscuring of the value of life stories wrought with any measure of thoughtfulness. Stories that not only distract us, remove us for a time from the pressing matters of our existence, but inevitably carry us back to a reflection on those same lives. For however banal, uneventful, or ordinary... be it ever so humble, there is no story like THE story: the master narrative; the story of our life.

Like a good piece of conceptual art, Richard Linklater's engrossing, 166-minute Boyhood derives most of its power from its premise. Shot intermittently between the summer of 2002 and the fall of 2013, Boyhood follows Mason Jr. (Ellar Coltrane) and his family from the time he's a five-year-old boy until the outset of his college years. We see this soulful, questioning boy grow up before our eyes in just less than three hour and it's a moving experience.

In Boyhood, we see a lot of passing time heralded with young Mason's ever-changing hair styles - involuntary buzz cut to a kind of Texas Fauntleroy of girlish length and curl about the face still maintaining a good bit of its baby fat - not to mention those skirmishes of acne playing out on his adolescent face as it gains angle and definition. This photo album (or Flickr page) given motion is replete with built-in sentiment. There is also the boy himself. Linklater's premise might be watchable enough with any young actor as its lead, but Ellar Coltrane's subtle performance throughout provides a depth of feeling after which Boyhood itself sometimes quests with a little too heavy a tread.

Where Boyhood might tend to go wrong and where it ultimately succeeds is demonstrated quickly enough in the film's opening moments. We're made to regard one of those summer skies of brilliant cerulean and drifting, knowing cumulus. Over this timeless background the film's title appears in a kind of aw-shucks, pseudo-hand-written font. This to the accompaniment of the Coldplay's "Yellow." It's a precious little balloon that is voided of its warm air when the perspective switches to that of young Mason Jr., supine on his lawn. When Linklater lets his camera focus on the blue eyes and serious visage of Ellar Coltrane, he never goes too wrong. Mason Jr.'s face, like that summer sky he regards, seems lit from within and yet drifted by its own enigmatic clouds.

Fast enough on the heels of "Yellow," we see and hear Mason receiving the unwonted serenade a la Britney Spears from his older sister, Samantha (the director's daughter, Lorelei). Not long after that highly successful bit of annoyance, it's The Hives "Hate To Say I Told You So," as Mason and a young companion indulge in a bit of graffiti. Musical cues both to the early 2000's. When Sheryl Crow arrives at the party soon thereafter, it seems that Boyhood might be on its way to three hours of montage punctuated by interludes of significant dialog. Fortunately, Linklater lets the music drift into the background where it belongs and away from its rigid chronological moorings.

The mere audacity of Linklater's concept seems to be winning the director lavish praise that he hasn't quite earned. Boyhood is a great concept that the director doesn't always trust. Where many a film utilizes flamboyantly bad hair to illustrate the passage of time, Boyhood has the actual stuff. Lorelei Linklater - who settles into her role after a gratingly energized start - has had any number of styles and even colors immortalized, one bang-heavy arrangement particularly tragic. So it goes with Ellar Coltrane and his aforementioned extremes of style and length. Much more significantly, we see time playing out in most profound way: these kids grow up before our eyes. No elaboration is necessary.

And yet Linklater has the camera come to rest on several generations of video games and controllers with such conspicuous focus that you would think a product placement deal with Nintendo and others was in place. Similarly, Mason Jr. and some friends walk down a sidewalk, each one of them with a particular iteration of the Coke can in hand, the sort of consensus found only in advertising. This might not be quite the pages flying from calendar, the clock hands spinning madly around their circle in the hack films of yesteryear, but it's close.

As the writer/director model goes, Richard Linklater has usually distinguished himself much more as a writer who directs. Not necessarily a bad thing. Even something as seemingly experimental as Waking Life (I've not seen his adaptation of A Scanner Darkly) with its nervous animation is still mainly a film about conversations, still more verbal than visual. Through his varied body of work - drifting warily toward the Hollywood mainstream and back to his native Texas for stories set in that state - Linklater has been reliably competent director with occasional flashes of something more. Me and Orson Welles, for one, is a little-seen gem that you wish Hollywood could produce more often, an intelligent package of pure entertainment in which the director (he did not contribute to the film's script) draws the best out of his actors and presents a story to its best advantage. But for those who remember Richard Linklater, they are likely to remember words and not images.

The director's touch is not always light with the would-be-profound raw material of Boyhood. And even Richard Linklater, the normally rock solid writer and storyteller loses his way occasionally through the expanse of the story.

|

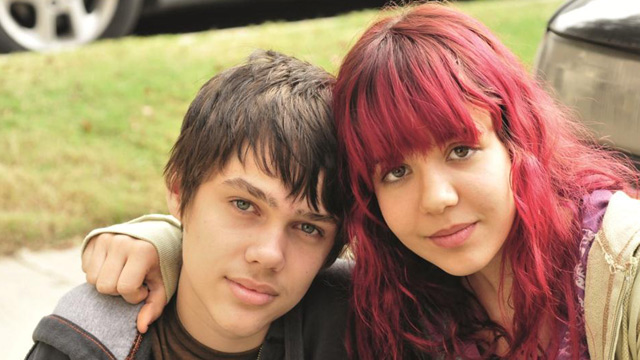

| Is she really going out with him? And him? Patricia Arquette and Ellar Coltrane in Boyhood. |

As Boyhood begins, Mason Jr. and his sister are being raised by their mother (Patricia Arquette), while their father (Ethan Hawke) is busy keeping maturity at arm's length in Alaska. As the mother tries to keep the family together and even return to college so they can all enjoy a better life, she marries not one, but two other men who celebrate their matrimony and responsibilities by becoming sour drunks. This is particularly the case with a college professor (Marco Parella) of the Arquette character. The two marry and join their families, but before long - in the grand tradition of mental health professionals or teachers who cannot begin to heed the sound advice they espouse - he's guzzling way more alcohol than soda in the plastic bottle he carries around the house, on his way to becoming a drunken, glass-hurling Great Santini. As is his easygoing way, Mason first greets the professor with a smile. But we subsequently see the boy looking on warily as the man and his mother flirt.

So it goes with the next candidate, a handsome, youngish veteran named Jim (Brad Hawkins) who somehow manages to win mom's affection and hand before seeking commiseration in too many cans of beer during off hours from his work as a correctional officer. As that relationship begins to develop, we once again see Mason look upon his mother's growing fondness with skepticism if not outright displeasure. This shot almost mirrors the earlier focus on Mason looking askance at his mother and Professor Bill.

While it may well be true that shrinks and teachers of psychology come off the mental rails as disastrously as anyone else, while mommies and daddies do sometimes make the same mistakes repeatedly, this repetition in Boyhood seems an excessive bit of rough road thrown in before mom and son can eventually arrive at a more satisfying place for both, much as the mother has to eventually face the sadness of her empty nest.

The most glaring shortcoming amidst all that goes right in Boyhood may well be a scene in which a teenage Mason and one of his contemporaries hang out with some older boys in a house under construction. Linklater does at least avoid obvious conflict or crisis - some sort of humiliating ritual; the circular saw blade being thrown into a section of drywall like a kung-fu star doesn't actually come to rest in some young body as you fear it might - in this scene, but nothing rings true in the execution. We hardly need an interlude of stilted dialog and clumsy line readings to demonstrate that boys often act and talk down to a very low common denominator of bravado when performing for each other in a group. It's a surprising misstep for a writer who has gotten this sort of thing so right in the past (at least as well as one remembers films like Slacker and Dazed and Confused...).

The men don't acquit themselves very well in Boyhood. We're given a pretty dubious sampling of fathers and would-be fathers. But with Mason Sr., Richard Linklater not only creates a character of complexity, but winds the story along an unexpected though no less realistic course. When he first reappears on the scene, the older Mason impresses one as an absentee father off an assembly line, bearing gifts and an exaggerated enthusiasm he seems unlikely to maintain. When the father does show up or drive off into a sunset of limited responsibilities, it's in a cherry GTO, the sort of starter object of love from which many men never seem to graduate.

But to our surprise, Mason Sr. sticks around and sustains an interest in his children, in having actual conversations. Easy enough, one might say, when you only have to parent every other weekend. And perhaps largely a matter of assuaging a guilty conscience. But as some men streak from mortality, others embrace the trappings of convention, perhaps a second shot at a family with all the energy with which they earlier scorned those things. Mason Sr. is this sort of man. Ethan Hawke hits truly upon all the fluctuations of this particular father, the bending of him by life into something that fits into his world.

The power and the pleasure of Boyhood is to watch its young protagonist question his way through those early years, rarely angry but also rarely happy, a fine, wavering line between his admirable skepticism and an unfortunate tendency to feel that nothing much can be trusted. A natural enough complexity in a boy who has had the ground so often shift beneath his feet. Richard Linklater generally tells this story well, renders dialog that make us believe Mason Jr.'s struggle and development. This is never more the case than some lovely exchanges between Mason and his high school girlfriend, Sheena (Zoe Graham, quite good), two intelligent young people trying to sort out the world and their feelings, not necessarily in that order.

Ellar Coltrane is well cast to carry this long film, through all the years and fluctuations in hair style. Throughout the eleven years condensed into 166 minutes, there a light in those blue eyes which tells us that life is happening right then and there.

Just how good is Boyhood? "A Moving 12 Year Epic That Isn't Quite Like Anything Else In The History of Cinema!" (exclamation mark added; about a dozen exclamation marks implied). So exults one version of the film's poster, quoting a gushing critic who apparently doesn't get out to the movies often enough. And, well...let's not get completely carried away.

Perhaps our overly-eager friend who shall remain nameless has never heard of English film directors Michael Apted and Michael Winterbottom. That's not easy as it might seem, as those talented directors have quite literally been all over the place, in subject matter as much as geography. Among his extensive and varied body of work, Mr. Apted continues with his fairly towering "Up" series that has followed a group of English children from the age of seven well into their sixth decade. For his part, the mercurial Winterbottom premiered Everyday in 2012, which depicts a man and particularly his wife and children during the five years of the husband and father's imprisonment.

Boyhood is neither unprecedented nor great, nor must be it to be worthwhile. It is essentially a mural to most film's neatly-framed pictures. To look upon the expanse of any mural rendered with a good degree of competence and style is to be a bit awed, to be carried away by the sweep of the thing. So it is with Boyhood. Linklater's mural generally does bear scrutiny, even if some of the detail reveals a common touch.

Seen another way, which might partially explain the inordinate enthusiasm with which it has been greeted, Boyhood is a big, green oasis in the particularly drought-ridden cinematic summer of 2014 (never mind that arid Texas ground so often on display). Sit down and watch this film and you are likely to be aware of its breadth, of the time being stretched and yet feel no hurry for the experience to end. Rather like life that way.

Beyond the story of Mason Jr., whom we leave in Big Bend National Park, tripping peacefully on mushrooms with a few fellow freshmen (this isn't quite the principals of Lawrence Kasdan's Grand Canyon looking awe-struck at the eponymous hole in the ground at film's end, but it does get perilously close), Boyhood will almost inevitably lead you to reflect upon the stealthy passage of time in your own life, when images from your youth might seem as incongruously fresh as something that happened just a few hours ago.

db

Comments

Post a Comment