There's a kind of cliche in the uninitiated looking at a work of modern art, perhaps a seemingly simplistic piece of conceptual art, and saying, "I could do that." True perhaps, but would it have ever occurred to you to do so, oh skeptical one? Such might be the case with a creation like Picasso's "Bull's Head." Where most would simply see an old bicycle seat and handlebars, the Spanish artist saw something else entirely. He saw a bull, his homeland's passion for corrida, no doubt a factor, consciously or not. And the rest is art history.

Rather less likely would such a "I could do that" pronouncement occur before the work of an old master, someone like Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. With Vermeer, there would not only be the matter of equaling the mastery of form, the very distinctive use of color, the extraordinary attention to detail. With the Dutch artist, there is also the uncanny presentation of light, captured with an almost photographic clarity. How did he do that, even the learned have asked? Who in their right mind would say "I could do that?"

Rather less likely would such a "I could do that" pronouncement occur before the work of an old master, someone like Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. With Vermeer, there would not only be the matter of equaling the mastery of form, the very distinctive use of color, the extraordinary attention to detail. With the Dutch artist, there is also the uncanny presentation of light, captured with an almost photographic clarity. How did he do that, even the learned have asked? Who in their right mind would say "I could do that?"Enter Tim Jenison. As the documentary Tim's Vermeer proceeds and we see the inventor with virtually no painting experience attempt to replicate the magic of the Dutch painter, he's not above questioning his own soundness of mind in taking up the seemingly impossible challenge. Years into the project, an endless series of days into the actual painting and nearly driven out of his wits in capturing the extraordinary physical details of textile and decoration within the work, he is asked if he would continue if not being filmed. "If we weren't makin' a film would I quit? Yeah...I would definitely find something else to do right now."

While not a great artist, nor even an amateur painter, Mr. Jenison is something of a genius, a not so old master in his own right. So his history of invention and innovation in electronics and computer hardware and software would seem to indicate. So too says his long-time friend, Penn Jillette. When Jillette heard that Jenison was going to attempt to paint Vermeer's "The Music Lesson," he decided to document the process. Jillette's partner in illusion, entertainment and all-purpose debunking, Teller, directed the film, with his larger and more audible partner providing narration. The duo hired a very able crew, including composer Conrad Pope, and otherwise, judiciously stayed out of way, training the camera on Jenison and let him go about his work.

That work, a painstaking construction of the room used for "The Music Lesson,"as well as the almost maddeningly detailed brush strokes required, make Tim's Vermeer nothing less than a meditation on the nature of art, on the meaning of genius.

Being a man of technology, Jenison was drawn to the incredibly ambitious project by the theory that the Dutch painter might have used a camera obscura to produce his vivid work. X-rays of Vermeer's paintings reveal no lines of tracing beneath paint. Similarly, no written documents survive to provide clues as to his process.

In his quest to determine how Vermeer might have produced that nearly photographic clarity in his work, Jenison was preceded, at least theoretically, by two men.

Professor Philip Steadman caused quite a stir in the art world when he published his book Vermeer’s Camera in 2001. Steadman investigated the theory that the artist had used an optical device (the camera obscura) that could project the image of sunlit objects placed before it with extraordinary detail. Steadman’s experiment used a technique known as “reverse perspective” which produced results not easily dismissed. He found that six of the Vermeer paintings he analyzed depicted the same room, the painter’s studio in Delft, and the geometry of the six was consistent with their being projected on to the back wall of the room using a lens and then traced.

To truly replicate Vermeer's process, Jenison not only constructed a replica of the very space and objects depicted in "The Music Room," but used the technology of the 16th century in the painting of the canvas, including the grinding of pigments for paint and the production of lenses for the camera obscura.

Jenison discovered early on that the camera obscura could take him only so far in in completing the projected image. Much as outlines could be traced, the wall projections rejected, in a sense, the matching of color, however much he might adjust the lens being used to transmit the painting's subject into the dark box of the camera obscura. In a discovery probably typical only of minds as supple and obsessive as those of Jenison, he realized in bed one night that the solution lay in a projection of the image through the lens to a mirror held above the canvas, allowing for a near-exact matching of color and form. He kept the lens but lost the dark box.

Jenison discovered early on that the camera obscura could take him only so far in in completing the projected image. Much as outlines could be traced, the wall projections rejected, in a sense, the matching of color, however much he might adjust the lens being used to transmit the painting's subject into the dark box of the camera obscura. In a discovery probably typical only of minds as supple and obsessive as those of Jenison, he realized in bed one night that the solution lay in a projection of the image through the lens to a mirror held above the canvas, allowing for a near-exact matching of color and form. He kept the lens but lost the dark box. There came also the realization over time that the that gradations of light in Vermeer's paintings - light from a partially shaded window brighter closer to its point of entry in the room; darkening almost indiscernibly as the beam extends away from that point of entry - could not be perceived by the naked eye. This confirmed by former Oxford don Colin Blakemore, an expert in neurology and optics. Yet more proof, it would seem, of the lens and mirror method, catching almost impossible detail in the virginal (the richly decorated keyboard in the Vermeer painting) and floor rug, as well as those gradations of sunlight across the top of the wall.

Documentaries live or die by the nature, the potential fascination of their premises, not to mention that of their human subject(s). Tim's Vermeer manages to succeed on both counts. The results of Jenison's years-long quest are history altering, if not mind altering. And the man himself has an unassuming authority, a compelling and often amusing mix of a dogged adherence to detail a surprising penchant to simply wing it at other junctures. The genius and the everyman seem to exist comfortably within the same practical clothing.

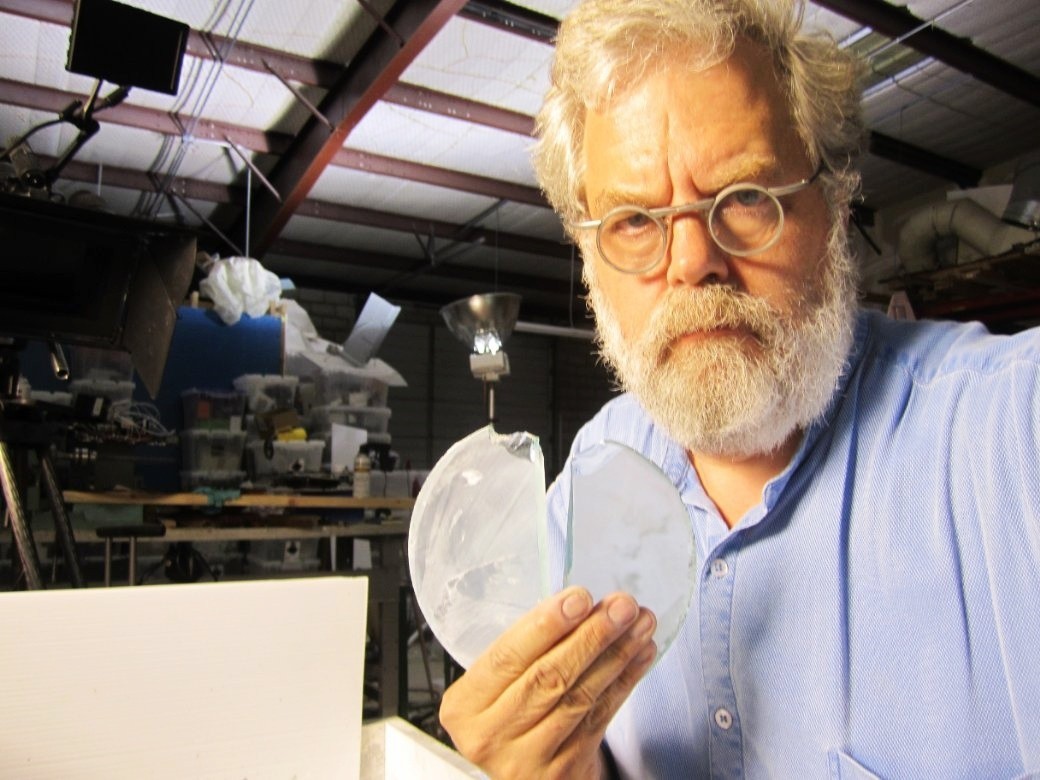

Documentaries live or die by the nature, the potential fascination of their premises, not to mention that of their human subject(s). Tim's Vermeer manages to succeed on both counts. The results of Jenison's years-long quest are history altering, if not mind altering. And the man himself has an unassuming authority, a compelling and often amusing mix of a dogged adherence to detail a surprising penchant to simply wing it at other junctures. The genius and the everyman seem to exist comfortably within the same practical clothing. Jenison has the professorial bearing of one of his former vocations. He also seems an appropriate figure to be scrutinizing the old masters, as he wouldn't look so out of place in a portrait by the likes of Frans Hals, draped in period dress, ruff encircling his neck beneath the dignified swath of white beard, perhaps primed with a few pints of beer to redden the cheeks. The Texan also looks very much at home with a viol da gamba propped against one knee and bow in hand, but tests the instruments with a few notes of"Smoke on the Water" (in younger days, he played keyboard in a rock band). The man's brilliance is evident, not only in solving mysteries about Vermeer's work that have existed for hundreds of years, but in adapting to painting, woodworking and the other skills necessary to recreate the music room, then somehow painting it with the precision of one of those old masters ("It took me about a half an hour to learn to operate a paintbrush" he says, to actor and long-time painter Martin Mull. "Congratulations, it took me forty years," deadpans Mull). And yet, with an enormous effort of research and construction behind him and the exacting days of painting ahead, he expresses a sentiment with which anyone could identify, "...this better fucking work."

The painting itself is incredibly exacting, all 130 days of it. At one moment of confession to the camera, Jenison notes, without irony, "this is like watching paint dry." This particularly the case with the decoration of the virginal and the ruthless detailing of the rug, in which Jenison ruefully realizes that seemingly every knot of fabric is rendered in the Vermeer painting. Days follow of what Jenison calls "painting dots," enthusiasm for the project a dubious memory, weary face falling into the palm of his hand.

Jillette imposes himself just enough to break up the potential monotony (of the documentary; the painter's monotony is real and all-too-obviously painful). When Jenison's daughter is home for spring break, she is recruited to portray the "little Dutch girl" in the painting. This she is able to do to an almost uncanny extent her father feels. But the model's work too is hard, forced to be still for long intervals, head sometimes held in place with a kind of clamp. Jillette notes in voiceover that no kid has ever been so happy to go back to school. Teller for his part (presumably) allows the camera some mobility, observing the girl's fingers rolling to fight off the tedium, or even better, hoisting a can of not-terribly-historically-accurate Diet Coke during a down moment, an amusing token of the convergence of worlds and eras.

Perhaps the greatest moment of comic relief in Tim's Vermeer occurs with Jenison explains how he had brought some exterior space heaters to warm up the converted San Antonio warehouse space where his "music room" was constructed. A little Internet research revealed that the heaters were perhaps not intended for internal use. But Jenison decided to go ahead, one of the man's occasional "fuck it" moments so at odds with the general meticulousness of mind with which he goes about his work. Sure enough, both he and friend helping with the project started to feel the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning. Time to step outside, he wisely decided.

Jenison also describes a last, almost shocking "fuck it" moment. When the painting is at last complete, he begins to important last step of applying varnish. After beginning the coating with the care typical of the 130 days of painting, the weary Jenison quickly decided to start "sloshing" the varnish over the picture. This is perhaps an exaggeration - Jenison's sloshing is probably another man's careful application - but none-the-less-surprising.

Fortunately, the "sloshed" varnish produced the desired effect. It provided a kind of crescendo to the painting, producing the clarity and brilliance so reminiscent of the master Vermeer. Jenison weeps at the result, presumably as much for the completion of years of work as the beauty of the object before him. It certainly does seem an amazing accomplishment.

Jenison takes his finished work to England to show to Hockney and Steadman. "I think it might disturb quite a lot of people," notes Hockney. In examining Jenison's canvas, he even points to a bit of detail and exclaims that it's better than Vermeer.

What does this all mean? It's eminently clear that - artist or not - Tim Jenison is an exceptional and compelling human being. But what of his apparent replication of Vermeer? Jenison says that he has come to feel a greater kinship with Johannes Vemeer as a fellow tinkerer, perhaps as much a 17th-century technologist as an artist. Probably not a characterization of the artist with which gallery and museum curators are comfortable.

Tim's Vermeer does nothing to debunk the vision of the old master, his finding something eternal in the arrangement of everyday objects and the color and light in which they are rendered. What Tim Jenison would seem to demonstrate is that a significant part of the equation - perhaps the greater part - of what is deemed artistic genius may simply be the will to complete what others cannot see or wouldn't dream to take on.

In this, one is reminded of Malcolm Gladwell's “ten-thousand-hour rule,” delineated in Outliers: "No one succeeds at a high level without innate talent...achievement is talent plus preparation. But the ten-thousand-hour research reminds us that the closer psychologists look at the careers of the gifted, the smaller the role innate talent seems to play and the bigger the role preparation seems to play." Or as Buddy Glass notes in J.D. Salinger's Seymour: An Introduction, "A good amount of sheer physical stamina is required to get through a first class poem."

Tim's Vermeer reminds us that the geniuses, the masters among us separate themselves not only in what they see: countless moves ahead on the static chessboard; poetry where others see merely the banal; glorious inventions where most can only see barriers. The Vermeers and even perhaps the Jenisons among us have to render what they envision, regardless the effort and thousands of hours necessary to realize that vision. Little wonder that so many go mad. Mr. Jenison seems to have survived his latest bout of obsession quite well, if Tim's Vermeer is any indication. And his wall now is home to the work of a recent master.

Comments

Post a Comment