It's so much easier to see the glory of war from a distance. From many thousands of miles away or the remove of decades. So much easier then to speak of greatest generations and by implication the glory of their efforts. A fairly prominent New York critic has praised Zero Dark Thirty for so thoroughly showing the dark side of war. As if there were any other side. Of course, any war will have its varied experiences, its moments of bizarre juxtaposition, its examples of bravery. But it's a grim, inhumane business.

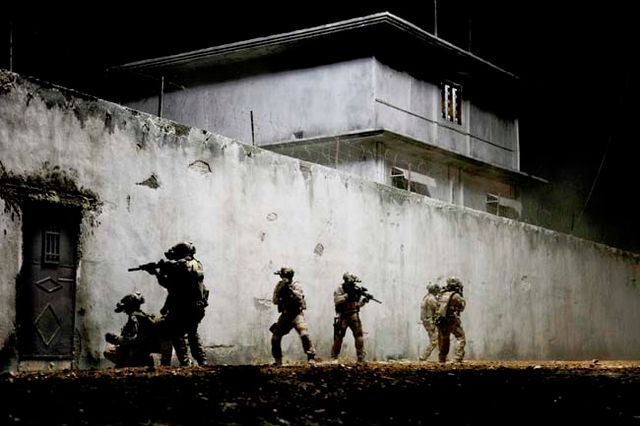

Zero Dark Thirty, written by Mark Boal and directed with brilliant assurance by Kathryn Bigelow, takes us right into the dark heart of the action. The war in question, in the rather Orwellian Newspeak of the previous (and present) administration, is the "war on terror." At times this action is quite slow, the following of leads and suspects over many years, the interminable wait to make decisive moves. At other key junctures, the action is extremely tense and of the moment: a sudden explosion anticipated or coming as a jarring surprise; the lonely, methodical move by Navy SEALS, seen in the green light of night vision goggles, through the Pakistani compound that proved to be the final hiding place of Osama Bin Laden, punctuated by explosions and bouts of gunfire; several scenes showing the torture of detainees at "black sites" by CIA agents.

Those torture scenes have generated the most controversy around the making and release of Zero Dark Thirty. However, what screenwriter Boal and director Bigelow have done with all of the particulars of this "story of history's greatest manhunt for the world's most dangerous man," some by their nature quite cruel, others seemingly valorous, is respect their audience enough to let them make up their own minds about the morality of what they're seeing, of the many examples depicted of America pursuing its policies and meting its revenge since September 11, 2011. A lot of ground is covered in Zero Dark Thirty's 157 minutes, but there's not much glory to go around.

It might be too much to say that Zero Dark Thirty is part documentary, part fictional feature, but it is a deft mix of the real and the perforce fabricated. Jessica Chastain plays a CIA agent known simply as Maya. If there was a CIA agent who tenaciously clung to the lead that finally led to Bin Laden, we may never know the real identity of that person for her own safety. So we have the fictional Maya, who early in Zero Dark Thirty arrives at one of the CIA's secret black sites in the Middle East. There she is met by a more veteran field agent, Dan (Aussie Jason Clark, late of Lawless), who's in the midst of trying to wring information out of a detainee, Ammar (Reda Kateb). Hungry and sleep-deprived, with a face that seems partially swollen from beating, Ammar has ropes attached to each arm which are suspended from the ceiling of what looks like a windowless Quonset hut.

"When you lie to me, I hurt you," says agent Dan before subjecting the woozy Ammar to confinement in a small box or pressing him to the floor for a round of the now-notorious waterboarding. What's surprising about the latter is how initially tame it looks as a form of torture. A cloth is placed over the Ammar's head and then water is poured steadily down on the face. It no longer seems a tame practice when we see the cloth removed and the face of the coughing, sputtering man who's fighting the "dry drowning" and other effects of the torture.

The inexperienced field agent Maya finds all of this difficult to watch at first. But any doubt about her tenacity evaporates when she is left alone with the suspect, who begs for her intervention. "Please help me," he implores. After walking unsurely toward the weary man, Maya says, "You can help yourself by being truthful," before stepping purposefully back. It's hard to say whether Maya's initial reaction is one of simple distaste or moral revulsion at what's she's witnessing. But she seems to harden to what she and her fellow agent would seem to deem necessary to accomplish their mission, all the more so after one attack on a CIA site in Afghanistan - mirroring the actual deadly 2009 Camp Chapman attack - which results in the death of several agents.

In Zero Dark Thirty, Jessica Chastain is called upon to embody tenacity in much the way Terrence Malick had her represent a benevolent grace in The Tree of Life. In neither character is there revealed any significant depth or complexity. But with Zero Dark Thirty's Maya, that's sort of the point. A single-mindedness, a pushing to the side of larger issues of philosophy or morality, would seem to be an effective mode in which to operate in such a dangerous, uncertain world. This film written by Mark Boal and directed by Kathryn Bigelow, is not the advertisement or apologia for torture which some have claimed it to be. But there is an implication that to pursue fanaticism a kind of equal fanaticism is called for. Or perhaps, it was one symptom of our country's pathology post-9/11 that such a mindset gained footing.

The criticism most apt to stick to Zero Dark Thirty is Boal's shaping the story in such a way as to telescope the swirling atmosphere of seemingly infinite amounts of information down to its focus on one lead - a courier who ultimately leads the C.I.A. to the compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan where Osama Bin Laden was hiding - and the many agents who worked to track down the al-Qaeda leader down to just one woman. This the woman who says after the attack on agents in Afghanistan, including a fellow female agent with whom a friendship had slowly developed, “I’m gonna smoke everybody involved in this op. And then I’m gonna kill bin Laden.”

|

| Cue the Ennio Morricone music? Jessica Chastain as the tenacious agent Maya in Zero Dark Thirty. |

Much as Mark Boal's story might narrow itself in terms of character and plot, there is still an apt form following form. Leads develop and are pursued, often with the passage of months or years. The most explicit expression of this frustration takes place after Maya has returned to the C.I.A. Headquarters. After she has made known to her superiors what she believes to be the location of "USL," as she comes to refer to her target, she takes to writing the days that have passed on the office window of her superior at Langley, George (Mark Strong, part of an excellent international cast) in red dry erase marker. Less dramatically, at least after the early torture scenes, a considerable amount of the film is devoted to the slow development of the search, complete with what appear to be dead ends. There are subtle examples and lingering implications that this distillation we're observing is but part of something larger, a continuum of years and agents.

That main lead to which Maya clings is the pursuance of Abu Ahmed, the courier entrusted to pass messages from Bin Laden to Abu Faraj al-Libi, an alleged senior member of al-Qaeda. At first this seems quite plausible. Then Maya is told that Ahmed has long been dead. Only the diligence of another agent, poring through a backlog of intelligence, reveals that Ahmed might well be alive with the real identity of Ibrahim Sayeed.

That main lead to which Maya clings is the pursuance of Abu Ahmed, the courier entrusted to pass messages from Bin Laden to Abu Faraj al-Libi, an alleged senior member of al-Qaeda. At first this seems quite plausible. Then Maya is told that Ahmed has long been dead. Only the diligence of another agent, poring through a backlog of intelligence, reveals that Ahmed might well be alive with the real identity of Ibrahim Sayeed.At various points in the long ebb and flow of promise, Maya has to endure the skepticism of colleagues and superiors and be admonished that the agency and the country have other priorities as well. Much as the focus on the one lead - as opposed to the several that led to the discovery of Bin Laden - is a dramatic device, it reveals a mindset which surely is not absent from agencies like the C.I.A., from the upper reaches of governments. Whether to hoodwink a gullible public or to simply clutch at a shaky version of reality for more personal reasons, unlikely stories are floated, far-flung narratives put forth like advertising campaigns. Of course, not so long before the events of Zero Dark Thirty, there was the grand fiction that was Saddam Hussein's Weapons of Mass Destruction, incubated in the Bush Administration and flogged by the likes of Tony Blair and Colin Powell at the United Nations (a particularly sad iteration, in that it didn't really seem Powell's narrative at all).

After it appears the courier lead has died (or been dead for some time), one of Maya's more sympathetic fellow agents consoles her by telling her that he really believed in that lead, as if speaking of a promising boyfriend who died tragically young. And after the long-sought Ahmed/Sayeed is finally identified and followed to the compound, revealing the possible location of "USL," Maya attends a briefing in Washington, presided over by a top official in the Obama Administration (James Gandolfini, apparently as C.I.A. director Leon Panetta). After all of the information has been presented, Maya says, "I'm the motherfucker who found this place." Here, Boal - and Bigelow by extension - allow themselves to be carried away a bit. But much as such dramatic exclamations are the stuff of Hollywood film, there is behind the bold words an attitude probably not so foreign to people under great duress to produce results in their job, particularly for the likes of C.I.A. agents post-9/11.

|

| Director Kathryn Bigelow |

The star of this show, more the screenwriter Mark Boal or actress Jessica Chastain at its center, is director Kathryn Bigelow. And yet, this is hardly an auteurish effort. Throughout the 157 minutes of Zero Dark Thirty, there are virtually no directorial flourishes. Very likely the two best jobs of helming films by American directors in 2012 were Ms. Bigelow here and Paul Thomas Anderson with The Master. In both cases, the directors served their stories and disappeared behind brilliantly assured storytelling. The most confident voice is often the quietest one in the room. Of course, neither was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director.

Also snubbed by the seers at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was Ben Affleck for Argo. In significant ways, Zero Dark Thirty is the anti-Argo of 2012; it is Argo for grownups.

Compare confrontation scenes in the two films, the quiet hallway exchange between government officials in Bigelow's film with a similar confrontation in Argo, in which Bryan Cranston shouts at a superior, "DO YOUR FUCKING JOB!" Compare the methodical storytelling and even conclusion - the raid on the compound in Pakistan; a sequence rife with potential for saber rattling and flag waving if ever there was one - in Zero Dark Thirty to the climactic airport scenes in Argo. In the latter, virtually everything that happens in the Tehran airport was fabricated for the film, in a story whose bare bones truth was already rich with drama, told with skill for much of its length, finally stretched the point of absurdity, as Revolutionary Guards pile in a vehicle to chase the plane with escapees down the runway. Compare if you will the flag waving we do see at the end of Argo. After we have practically seen agents high-fiving at Langley, agent Mendez reunites with his estranged wife while an American flag is seen to wave its approval in the background. Compare that to the sober conclusion of Zero Dark Thirty. I was in a fairly well attended Saturday night screening of Ms. Bigelow's film. Its end was met with nothing but reflective silence.

After a choppy start, Maya's first briefing in the undisclosed Middle Eastern location, the scene like a bad Robert Altman film with its difficult to comprehend, overlapping dialog for no good reason, most everything that follows is sure and seamless. What Bigelow does expertly, even better than she did in The Hurt Locker, is place us almost tangibly in a myriad of situations. We are made to feel the paranoia of a car's approach to a compound in Afghanistan. Does it carry an explosive device? We feel the tension of a "ground" agent driving around a teeming Pakistani marketplace, trying to finally identify the long-sought Ahmed/Sayeed, wondering who might be following his progress amongst the crowd. And hardly least of all, there is the extended sequence of the flight of helicopters into Pakistan, carrying the now-famous SEAL team. There is almost no bravado here, just the daunting mission at hand and all that could go wrong. We get a sense of how lonely it must have felt to have been dropped into that Pakistani compound in the night, particularly after one of the helicopters crash landed. Bigelow delivers all this without busy editing or other shortcuts to ratchet tension.

That ground agent who finally identifies the courier to Osama Bin Laden is played by Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez. I've read nothing about the casting decision of Ramirez. It might just be another case of a talented international actor assuming a role in Zero Dark Thirty. However, it is a considerable coincidence that Ramirez also played the title character in Olivier Assayas Carlos, another very deliberate - 339 minutes in its longest version - film about the career and downfall of terrorist "Carlos the Jackal." With Zero Dark Thirty, Ramirez finds himself on the other side of governmental authority, if not the law. But I can't help wondering if someone making decisions on Zero Dark Thirty, whether Bigelow, the head of casting or someone else, relished the notion of hiring the actor who played a notorious international terrorist to play the pursuer of another. As if all of this is just a monumental, internecine game played by people grasping for power and attention.

Regardless of what factual details we might know that are inconsistent with the fiction of this film, regardless of those that might later be revealed, Zero Dark Thirty is likely to endure as a document of the dire spirit of this age. Certainly it should endure for Kathryn Bigelow's great skill in filming one of the major stories of this time. Beyond politics, beyond the morality of waging any war, inflicting any destruction, death or torture, it certainly has been, as one of the Navy SEALS says working his way through that fateful Pakistani compound, "a fucking mess."

db

Comments

Post a Comment