Finally, a story. So reads the screenwriter's epitaph, according to the old joke. That dilemma, the unending quest for a good story, is one that Marty (Colin Farrell), an Irishman living in Hollywood, understands all too well. His agent calls to remind him that his next screenplay is due. Unfortunately, Marty has made little progress, beyond a bold if rather literal title: Seven Psychopaths. Thus begins the film within a film, or perhaps film about a film by another Irishman, Martin McDonagh, also in Hollywood and lapsing into a major sophomore slump after his surprising debut, In Bruges (2008). Seven Psychopaths might be only the second full-length feature for Mr. McDonagh, but for his part, he already seems to be a writer running desperately short of ideas.

The subject matter in Seven Psychopaths, aside from the screenwriter's dilemma and, well, psychopaths, is hit men. Such was the subject of McDonagh's vastly more original debut, In Bruges. Perhaps it constitutes a bit of progress for the writer/director that Seven Psychopaths involves, at least in flashback, hit women. This despite one of the film's more energetic attempts at humor, delivered by Marty's friend Billy (Sam Rockwell), "You can kill a hundred women in a movie, but you can't kill a fluffy dog." It's a rule that Seven Psychopaths both sets forth and follows with dire adherence. I am happy to report that no harm comes to the fluffy dog in this film, Bonny the Shih Tzu (played by Bonny, who is in fact a Shih Tzu; I hope poor Bonny isn't being typecast).

The subject matter in Seven Psychopaths, aside from the screenwriter's dilemma and, well, psychopaths, is hit men. Such was the subject of McDonagh's vastly more original debut, In Bruges. Perhaps it constitutes a bit of progress for the writer/director that Seven Psychopaths involves, at least in flashback, hit women. This despite one of the film's more energetic attempts at humor, delivered by Marty's friend Billy (Sam Rockwell), "You can kill a hundred women in a movie, but you can't kill a fluffy dog." It's a rule that Seven Psychopaths both sets forth and follows with dire adherence. I am happy to report that no harm comes to the fluffy dog in this film, Bonny the Shih Tzu (played by Bonny, who is in fact a Shih Tzu; I hope poor Bonny isn't being typecast).The real and attempted make believe worlds of the screenwriter involved in untoward convergence is rich enough with possibility. But just as Mr. McDonagh's first film is far more original than his current effort, this sort of worlds colliding theme has been done better elsewhere. There was the Cohen's everything and the kitchen sink version of the writer coming undone in Barton Fink (1991). An even better example of a writer struggling to tell his story, invaded not only by his would-be fiction but another version of himself played out in Charlie Kaufman's screenplay for Adaptation (2002 - the writer was paired felicitously with director Spike Jonze for that film).

The implausibility and, frankly, the immaturity of Seven Psychopaths might be more easily overlooked if it simply did a better job of entertaining. There is so little of the wit and freshness that McDonagh demonstrated with In Bruges. Take just one segment of McDonagh's first feature, in which the younger hit man Ray (Farrell) goes on a date with a lovely young woman Chloe (Clemence Poesy). It turns out to be a very memorable date, with, as Ray later reckons, two incidents of extreme violence. These involve Ray clocking both an American (or so he thinks) husband and wife in a restaurant and later getting the better of Chloe's skinhead partner in crime by firing a gun full of blanks in his face. Those episodes of violence are much more the exception than the rule for In Bruges before the showdown at film's end. And even those interludes are more antic than unsettling, in each case a kind of physical exclamation point to the humorous, alternating current of conversations taking place. Seven Psychopaths might want to pass itself off as a kind of meta film, but with the greater insistence of violence in this second feature, for all the convolutions of film within film, there seems a desperation to hide what is the fact that there's not much going on. Pay no attention to that screenwriter behind the curtain, for he has nothing to say.

|

| Do these men have any reason to smile.? Well, yes. They're not watching Seven Psychopaths. They're watching a good film. It's called Violent Cop, by Takeshi Kitano. |

Doing the shooting and other forms of mayhem in Seven Psychopaths is a cast of likely lads. Perhaps a little too likely. A couple of generations of cinematic live wires have been rounded up, Farrell, Sam Rockwell, Woody Harrelson, Christopher Walken and Tom Waits, the more notable participants.

|

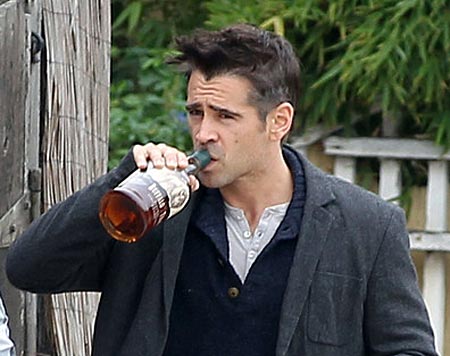

| Colin Farrell, imbibing a bit of Irish legacy, if not Irish whiskey in Seven Psychopaths. |

Sam Rockwell, usually a shortlister for any deliberation of American actors needed to play some shade of crazy, is Marty's friend Billy. Billy, as we are to find out, is two of the seven psychopaths, so very clever is the machinery of McDonagh's plot. Mr. Rockwell is certainly the man for the job. But as is the case with all the estimable talent involved, fuller roles would better serve the actors as they would the film. Rockwell has been able to do more elsewhere in the likes of Moon, or Matchstick Men, or the outright darkness of his disturbed husband in Snow Angels.

Much of the trouble in Seven Psychopaths is brought about by the theft of the aforementioned fluffy dog, who belongs to gangster Charlie Costello (Harrelson). Costello is clearly a man who subscribes to the kill women but no cute dog shall perish rule. The fluffy, agreeable Bonny seems to be the only living thing that arouses any sentiment in the man. It is the part-time vocation of Billy and Hans Kieslowski (Christopher Walken) to steal the dogs and return them for reward. The shifty Billy, lurking in popular spaces like the La Brea Tar Pits, steals the pooches, while the respectable-looking, older Hans returns the beloved pets to their relieved owners, generally all-too-happy to press the reward money into his hands. With the unwitting theft of the gangster's dog, Billy and Hans pull one dognapping too many.

The presence of Walken and Tom Waits are the more gentrified examples of the straight from crazy central casting choices that populate Seven Psychopaths. Had the film been made 15 or 20 years ago, Dennis Hopper would have probably answered the psychopathic role call as well; at the very least he would have been sought out. It's saying a lot, but Waits plays one of the more ridiculous of the psychopaths, Zachariah Rigby, a killer who hunts serial killers. This he does in flashback with an avenging African American wife, Maggie (Amanda Warren). In present-day Los Angeles, Zachariah, ever coddling a white rabbit (pretty crazy, no?), answers Billy's newspaper ad for psychopaths. This to give his friend Marty some material for his slow-developing screenplay.

Surely, we can find better work for Christopher Walken to do at the age of 69 than his role in Seven Psychopaths, sporting a coiffure a la Kramer and made to spout expletives as if trying to launch unwanted bran flakes from his mouth, the result making him sound more like an elderly victim of Tourette Syndrome than any sort of criminal. Actually, Walken has found better work recently, demonstrating the considerable and too-rarely utilized dignity he brings to bear as the elder statesman cellist in Late Quartet.

Walken does get a rare opportunity to do some acting in Seven Psychopaths in a hospital waiting room scene. He sits down opposite the Costello, knowing the gangster has just killed his wife as part of the hard target search for his beloved Shih Tzu. Hans' wife, Myra (Linda Bright Clay) had been receiving treatment for cancer. That fact and the tenderness of a scene between Hans and Myra are very jarring attempts at pathos in a script that doesn't come close to handling the changes in tone. One of the few pleasures to be had in Seven Psychopaths is watching Walken's eyes in this scene in which he squares off with Harrelson, sizing up the thug. Charlie Costello at this point doesn't realize that he's facing the man for whom he's been so ruthlessly looking. For a moment, we see a bit of that old dark magic from Walken: a little electrical storm of the eyes which signals a kind of controlled, almost bemused malice. It's reminiscent of another scene Walken played with the aforementioned Dennis Hopper in True Romance (1993). Unfortunately, what precedes the scene and all the foolishness that follows leave a small island of what might have been. It's later remarked that Hans is taking the death of Myra with amazing equanimity. Well, yes. Only because anything is possible with characters and a story which make no sense.

Walken does get a rare opportunity to do some acting in Seven Psychopaths in a hospital waiting room scene. He sits down opposite the Costello, knowing the gangster has just killed his wife as part of the hard target search for his beloved Shih Tzu. Hans' wife, Myra (Linda Bright Clay) had been receiving treatment for cancer. That fact and the tenderness of a scene between Hans and Myra are very jarring attempts at pathos in a script that doesn't come close to handling the changes in tone. One of the few pleasures to be had in Seven Psychopaths is watching Walken's eyes in this scene in which he squares off with Harrelson, sizing up the thug. Charlie Costello at this point doesn't realize that he's facing the man for whom he's been so ruthlessly looking. For a moment, we see a bit of that old dark magic from Walken: a little electrical storm of the eyes which signals a kind of controlled, almost bemused malice. It's reminiscent of another scene Walken played with the aforementioned Dennis Hopper in True Romance (1993). Unfortunately, what precedes the scene and all the foolishness that follows leave a small island of what might have been. It's later remarked that Hans is taking the death of Myra with amazing equanimity. Well, yes. Only because anything is possible with characters and a story which make no sense.

The fact that both Hans and Zachariah both have African American partners seems a case of throwing the races together, both for a kind of unlikely bonhomie and the appearance that something more bold and real is actually happening here. Perhaps this is some sort of Irish thing of which I'm unaware. Perhaps it's just a provocative McDonagh thing. John Michael McDonagh, Martin's brother, also contrived to pair black and white, with much more interesting results, in his feature-length debut as a director, The Guard. Fortunately, that film turned out to be rather more than 48 Hours: Port of Call Connemara. There is a value, after all, in acknowledging and laughing at our differences, at stereotypes. The overall depth and intelligence of The Guard more than made up for it's occasional and facile set-ups for jokes about racial misunderstanding. The same cannot be said for Seven Psychopaths. When Costello arrives in Myra's room, he doesn't initially realize that she's Hans' wife. When the mental tumblers click into place, he says "So, the _____ married a _______." Given that Hans is Polish and Myra is African American, the epithets are hardly difficult to guess. Would a gangster say such a thing in such a situation? Very likely. Does McDonagh's film bear enough relation to life on Earth to justify such asperse realism? Perhaps not. People are clearly finding much to laugh at and otherwise enjoy in Seven Psychopaths. But so much here is like the work of a shock-value comedian.

|

| Sam Rockwell, looking understandably perplexed in Seven Psychopaths. |

One of Seven Psychopaths more successful jokes actually arrives in somewhat stealth fashion, ironic in a film that hardly trades on its subtlety. Billy, ever the eager if deranged puppy nipping at Marty's heels, is giving the hard-drinking screenwriter a hard time, explaining that such a penchant is the legacy of the Irish: "The Spanish have got bullfighting, the French have got cheese and the Irish have got alcoholism," he says. "And what do Americans have?, Marty asks. "Tolerance," Billy deadpans.

What America has given the world, if not a golden model of tolerance, is the gangster film. This tradition goes back to the early days of American cinema, Raoul Walsh's Regeneration (1915) maybe the earliest example. McDonagh obviously admires some of the more recent practitioners of the gangster genre like Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scoscese. We have in Seven Psychopaths, after all, a screenwriter named Marty and a character with the surname of Bickle who at one point has a brief, provocative discussion with his mirrored self. There's nothing wrong with admiring the better work of these directors. But to be influenced by Scorsese or Tarantino as a maker of this sort of film is somewhat akin to having as your greatest blues influences be - with all due respect to the guitar gods - Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page. One gets farther and farther removed from what is real.

There's plenty going on in Seven Psychopaths, but it's a lot of gunfire and talk about gunfire signifying nothing. All of this without even elaborating on the absurd in no good way story line of the psychopath who is a former Viet Cong soldier - perhaps McDonagh should have placed his own ad in the paper for good stories. All of this, alas, after the originality and promise of In Bruges.

McDonagh has said he shares his character Marty's weariness with stories about guys with guns. Let us hope. A slightly more literary Quentin Tarantino the world hardly needs. A Guy Ritchie with delusions of grandeur even less so.

McDonagh has said he shares his character Marty's weariness with stories about guys with guns. Let us hope. A slightly more literary Quentin Tarantino the world hardly needs. A Guy Ritchie with delusions of grandeur even less so. db

Comments

Post a Comment