George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), not so long ago a movie star, finds himself an anonymous figure in a crowd filling the lobby after an afternoon matinee, a talkie entitled "Guardian Angel", starring America's newest cinematic sweetheart, Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo). Poor George, as ever in the company of his loyal Jack Russel Terrier, is like a defrocked priest milling about this cathedral of the motion picture. Young people in the crowd pass Valentin by, oblivious to his fame as a star of silent cinema. Finally, an older woman smiles in recognition. George returns the smile, one of significantly of lower wattage than those he beamed during his heyday, but still enough to signify his gratitude at the acknowledgement. But no, he quickly realizes, the woman isn't responding to him, but the adorable pooch in his arms. After she expresses her admiration, George says, "If only he could talk!"

No need to worry about the cute dog, but much of The Artist, directed by Frenchman Michel Hazanavicius, finds George Valentin struggling, his fortunes sadly parallel to the depression economy of the United States, post-October, 1929. The transition from silent films to talkies in the late-1920's and early-30's may not have been particularly hard on the dog acting community, but it was hell on many of the human contingent who had made names for themselves in silent cinema. Numerous actors, even directors, because they would not or could not work in the talking pictures, found careers cut abruptly short.

It was partly a matter of acting style. "People are sick to death of those actors who mug to make themselves understood," says Peppy a little too sanguinely (she would quickly regret the remark) to a reporter on the eve of breakthrough as a leading lady, "Beauty Spot." Of course, it was also a matter of voices which didn't translate to the new style, those somehow grating or marked by a foreign accent deemed too much for the American market. Ultimately, George Valentin was probably doomed on both counts. The irony and one of the great pleasures of The Artist is that director Hazanavicius is able to employ two foreign-born actors to play the American actors at the center of this story.

To the degree to which they are known at all in this country, director Hazanavicius and his star Jean Dujardin are recognizable as the names and face behind the two French "OSS 117" spy send-ups. The Argentine-born Berenice Bejo, who happens to be the director's wife, also starred in the first of the two films, OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies. Clearly, in making The Artist, all had love and not lampoon on their minds

The sea change in the world of film from silents to talkies provides a particularly poignant setting for Hazanavicius to tell his story as another variation on A Star is Born. As it usually goes, it's the young woman, Peppy Miller who's the up-and-comer, while George Valentin is the fading star who finds the world moving forward without him. The respective trajectories of the two performers is treated with visual symbolism in a lovely stairway sequence, in which the two meet in Kinograph Studios. George is, of course, going down, while Peppy, after stopping to attentively speak to her idol, springs upward to join two men waiting for her ("Toys," she says dismissively, after George glances up at Peppy's fair-haired retinue).

Ms. Bejo, slight of frame and prominent of dark eyes, wears well her period frocks and chapeaux, much as she ably evinces both Peppy's offhand charisma and the depth of feeling she demonstrates for Valentin and the dying era he represents.

However taken, The Artist is curious title for Mr. Hazanavicius' film. It sounds either vague or strident, but fortunately is neither. The writer/director might be a great admirer of silent films, but if he set out to make a more simplistic statement of a lesser age succeeded a greater one, he wisely tempered his approach.

As seen at the onset of The Artist, both on screen in "A Russian Affair" and afterward hamming it up for an appreciate crowed and media, George Valentin is a vain actor who does plenty of mugging. We see him as he leaves his requisite mansion, giving a wave to a much larger than life portrait of himself on the wall. Valentin will later hide behind the mantle of artistic integrity when he refuses to make the transition to talkies, instead sinking much of his fortune (the rest is taken by the stock market crash) into another silent film in which both acts and directs, "Tears of Love." But clearly, our hero is no great artist; this is no Keaton, no Chaplin. Like Shakespeare's Richard II, he seems to find a soul only after he's usurped and made to reflect on his identity. Before adversity hits, George is more from Douglas Fairbanks mould, or from that of his relative namesake, Rudolph Valentino. Valentino, the "Latin Lover," avoided the dilemma of talkies by dying suddenly at the age of 31 in 1926, sending legions of his fans into mourning.

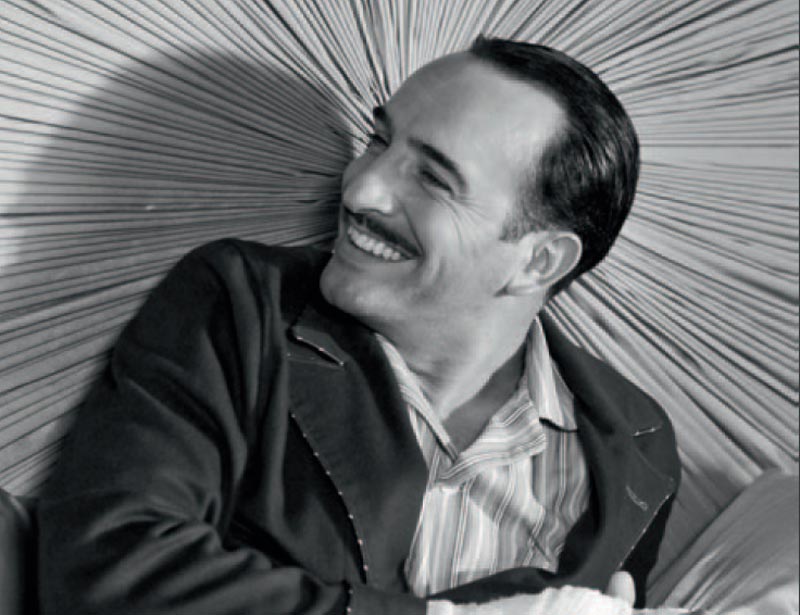

Dujardin's is a handsome, trumpeting face. The movie star smile is beamed with effortlessness. And he does have ample opportunity to do plenty of the mugging to which Peppy refers (his role as OSS 117 is also rich with such possibilities), with little distinction between film and reality while success is his. But as Valetin's fortunes change, we see the nuance of which that face is capable.

Valetin's potboiler films are produced at the aforementioned Kinograph studios, one of the subtle and not-so-subtle (a weary Peppy, early in her reign as a leading lady says to her attendants "I want to be alone," Garbo's immortal line from Grand Hotel) allusions to film and film history which crop up in The Artist. The Kinograph studio boss, Al Zimmer, is played John Goodman. Ignoring his considerable vocal skills, of which the Cohen Brothers have taken advantage in several of their films, Goodman is a natural as a silent actor with his expressive face and frame-filling physique.

As Clifton, Valentin's extremely loyal chauffeur and assistant, James Cromwell brings a hawkish gravity to his role, adding to the poignancy of his employer's decline. We see the two men in Valentin's small apartment after he's had to vacate his mansion. Clifton prepares their extremely modest foodstuffs with a formality befitting a far more elegant repast. "How long since I've paid you, Clifton, George asks. "One year, sir," is the answer. George then fires Clifton so me might find actual paying employment. Clifton initially waits by the curb with the car like a loyal dog waiting for command. He eventually leaves, but is never far away. The chauffeur is essentially the human companion to Valetin's Jack Russell. As for the pooch, the presence of adorable animals in film, like cute children, can fast become cloying. But the talent and charm of Uggie, the Jack Russell in question, can be denied by only the most resolutely opposed to actors of such considerable fur. The dog is good.

|

| For your consideration...Uggie. |

The Artist's varied score is by Ludovic Bource. Ranging from solo piano to swelling orchestral pieces, it dances its way through several decades of Hollywood musical history; touches of French lyricism keep the step pleasingly light. The one occasion when the soundtrack varies from the purely instrumental coincides with a montage that depicts Peppy's ascension to stardom (and by implication, the primacy of the talking picture). The charming, tinny voice we hear singing "Pennies From Heaven" sounds like the ghost of Blossom Dearie, but it's actually Rose "Chee-Chee" Murphy.

Mr. Bource gets to take out the orchestra and open up the throttle to accompany what is The Artist's most imaginative sequence, one that might well be entitled, "The Nightmare of Sound." So it must have seemed for many silent film actors. Valentin is in his dressing room and knocks over a bottle on a makeup table. Aside from the film's score, this is the first sound we hear in The Artist. Much to his surprise, George hears it as well. Another bottle, same result. Even the Jack Russell chimes in with a bark. Now alarmed, the actor steps outside onto the studio lot. Chorus girls pass and assault him with cackling laughter. More chorus girls and more laughter. Valentin is the only thing in this world that does not produce sound; he still can't talk. Finally, a feather drops from the sky and hits the ground to the sound of a bomb explosion.

An earlier scene, also in Valentin's dressing room, is emblematic of The Artist at its loving, graceful best. The starstruck Peppy sneaks into her idol's room to leave a note. When she sees Valentin's top hat and tails hung on a coat rack, she can't resist a touch. While not as inventive perhaps as "The Nightmare of Sound," what follows is so perfectly filmed and handled with such finesse by Ms. Bejo, that a simply cheeky episode becomes something much more deeply expressed. With her arm curled into the right arm of the jacket and around her waist, it's an embrace not only of Peppy's idol, or the man George Valentin, but a beautiful symbol of an ardor for the movies in general. The image of the empty formal attire will later find a melancholy echo when a destitute George looks wistfully at a tuxedo in a shop window, as the reflection of his head is superimposed atop the jacket.

Mr. Bource gets to take out the orchestra and open up the throttle to accompany what is The Artist's most imaginative sequence, one that might well be entitled, "The Nightmare of Sound." So it must have seemed for many silent film actors. Valentin is in his dressing room and knocks over a bottle on a makeup table. Aside from the film's score, this is the first sound we hear in The Artist. Much to his surprise, George hears it as well. Another bottle, same result. Even the Jack Russell chimes in with a bark. Now alarmed, the actor steps outside onto the studio lot. Chorus girls pass and assault him with cackling laughter. More chorus girls and more laughter. Valentin is the only thing in this world that does not produce sound; he still can't talk. Finally, a feather drops from the sky and hits the ground to the sound of a bomb explosion.

An earlier scene, also in Valentin's dressing room, is emblematic of The Artist at its loving, graceful best. The starstruck Peppy sneaks into her idol's room to leave a note. When she sees Valentin's top hat and tails hung on a coat rack, she can't resist a touch. While not as inventive perhaps as "The Nightmare of Sound," what follows is so perfectly filmed and handled with such finesse by Ms. Bejo, that a simply cheeky episode becomes something much more deeply expressed. With her arm curled into the right arm of the jacket and around her waist, it's an embrace not only of Peppy's idol, or the man George Valentin, but a beautiful symbol of an ardor for the movies in general. The image of the empty formal attire will later find a melancholy echo when a destitute George looks wistfully at a tuxedo in a shop window, as the reflection of his head is superimposed atop the jacket.

The Artist captures not simply the end of one movie-making era giving way to another, but a period in which the art form had the world in its thrall. Silent films were going the way of history. So too was the ritual of going to the movies at its most grand. As the U.S. economy crashed, the great movie palaces were no longer built. In the decades that followed, particularly after a surge in attendance after World War II, many would be demolished as television and other forms of entertainment made their claim upon our time.

The motion picture seems in no threat of extinction, much as our attention is drawn to smaller and smaller screens (the exception to the trend being our larger and larger televisions). There is also the matter of the increasing recording, projection and (amazingly expensive) storage of digital films. Given the ever-fluid state of technology and all the forms of distraction that clamor for our attention, it's hard to know if we're at a similar crossroads in terms of how we see films and what they might be. With that uncertainty at least in mind, one regards a film such as The Artist, one that celebrates not only film history but its continuity in such a graceful manner...with....as George Valentin says in the only words we hear him utter, "With pleasure."

db

The_Artist_6.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment